S6: Data-Driven (ML) Analysis

This notebook has three sections:

[1]:

# This cells setups the environment when executed in Google Colab.

try:

import google.colab

!curl -s https://raw.githubusercontent.com/ibs-lab/cedalion/dev/scripts/colab_setup.py -o colab_setup.py

# Select branch with --branch "branch name" (default is "dev")

%run colab_setup.py

except ImportError:

pass

[2]:

import cedalion

import cedalion.data

import cedalion.sigproc.quality as quality

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import scipy as sp

import xarray as xr

from cedalion import units

import cedalion.sigproc.physio as physio

import cedalion.sigproc.motion as motion

from cedalion.sigdecomp.unimodal import ICA_ERBM

from cedalion.sigproc.frequency import sampling_rate

from cedalion.sim.datasets.synthetic_fnirs_eeg import (

BimodalToyDataSimulation,

standardize,

)

# Limit display to show 3 items at each edge, then "..."

np.set_printoptions(threshold=20, edgeitems=2)

xr.set_options(display_expand_data=False)

# To reaload packages and modules automatically.

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2

Multimodal Source Decomposition Methods on Simulated fNIRS-EEG data

In this tutorial, we show how different multimodal source-decomposition methods can be used on an example toy fNIRS-EEG dataset to extract the underlying common (neural) sources. In particular, we cover Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), its regularized and temporally-embedded variants, and the multimodal Source Power Co-Modulation (mSPoC) algorithm from [Dähne, et.al. 2013]. All these methods can be found in the

cedalion.sigdecomp.multimodal package.

[3]:

# Define helper plotting function for later use

def plot_source_comparisson(

sx_power, sy, sx_power_model, sy_model, corrx, corry, corrxy, title

):

"""Plot comparison between original and reconstructed sources."""

fig, ax = plt.subplots(2, 1, figsize=(12, 4), sharex=True)

ax[0].plot(sx_power.time, sx_power, label="sx_power", color="red")

ax[0].plot(

sx_power_model.time,

sx_power_model,

label="sx_power reconstructed",

color="blue",

)

ax[0].set_title("Sx | Correlation: {:.3f}".format(corrx))

ax[0].set_ylabel("Amplitude")

ax[0].legend()

ax[0].grid()

ax[1].plot(sy.time, sy, label="sy", color="green")

ax[1].plot(sy_model.time, sy_model, label="sy reconstructed", color="orange")

ax[1].set_title("Sy | Correlation: {:.3f}".format(corry))

ax[1].set_xlabel("Time")

ax[1].set_ylabel("Amplitude")

ax[1].legend()

ax[1].grid()

plt.suptitle(

f"{title} Reconstructed Sources | Correlation: {corrxy:.3f}", fontsize=16

)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

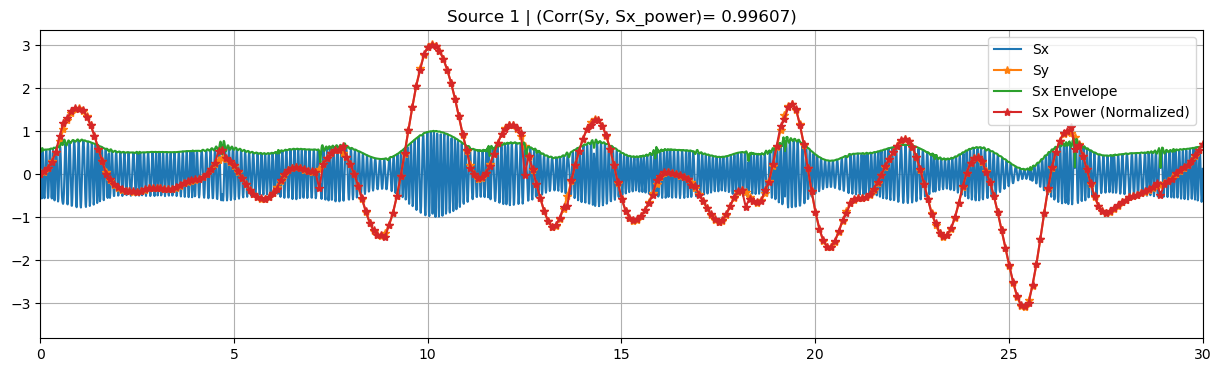

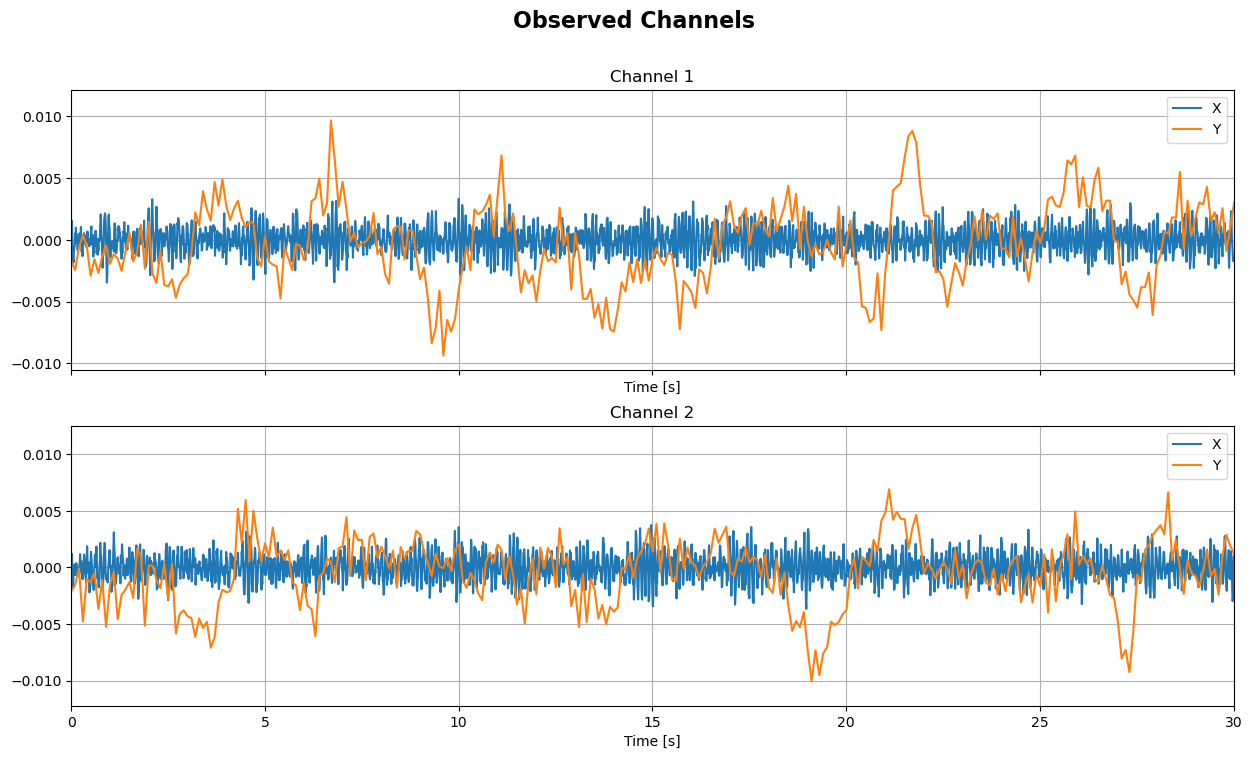

Simulated Dataset

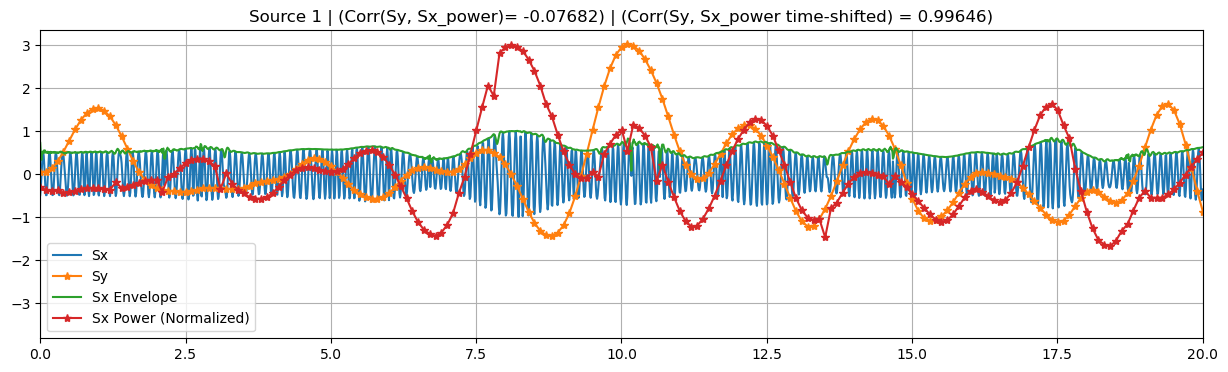

For the simulated data we follow a small extension of the approach presented in [Dähne et al. 2013] that can be found whithin Cedalion, inside the sim.datasets.synthetic_fnirs_eeg module. #### Brief toy data description: EEG (\(x\)) and fNIRS (\(y\)) recordings are generated from a pseudo-random linear mixing forward model. Sources \(s_x, s_y\) are split into background (independent between modalities) and target (co-modulate

between modalities). Each EEG background source is generated from random oscillatory signals in a given frequency band multiplied by a slow-varying random amplitude-modulation function. The latter is the envelope of \(s_x\), and it serves as an estimate for the source bandpower timecourse. fNIRS background sources are generated from slow-varying random amplitude-modulation functions, using the same approach as for the envelope of \(s_x\). The target sources are built using the same

technique, but this time the same envelope used to modulate \(s_x\) is used as the fNIRS source \(s_y\). The \(s_x\) target sources can be also time-lagged (dT \(> 0\)) with respect to the target source \(s_y\) to simulate physiological delays between modalities. Upon simulation, fNIRS sources and recordings are downsampled to a new sampling interval, a.k.a. epochs, T_epoch.

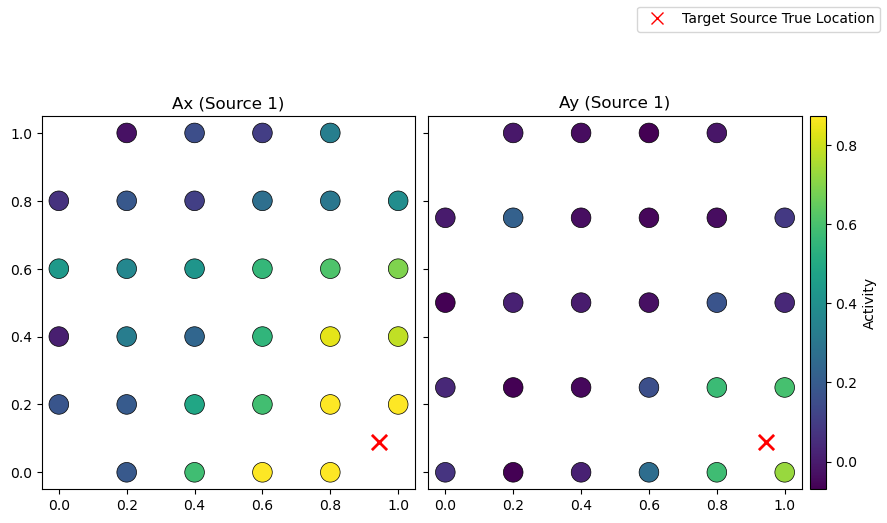

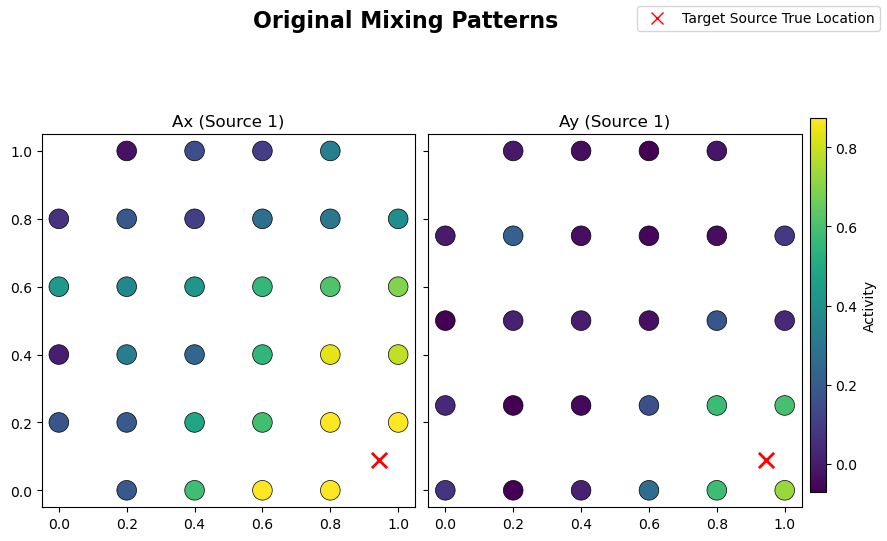

Random background mixing matrices \(A_x\) and \(A_y\) are built using normal distributions, while we use Gaussian Radial Basis Functions (RBF) plus white noise to generate the ones for target sources. The latter approach gives the spatial patterns a more realistic local structure, by using the same center for the RBF for \(A_x\) and \(A_y\).

The SNR can be tuned with the gamma parameter, which regulates the relative strength between target source and background source contributions in channel space. The exact relationship between SNR [dB] and gamma is given by \(20 \ log_{10}(\gamma)\).

The EEG recordings and their channel-wise powerband timecourses can be accesed via the x and x_power attributes. The former has the full sampling rate used during simulation (i.e. rate), while the latter has been downsampled so to be in the same time basis as the fNIRS recordings, y, and therefore directly comparable. The simulated target sources are contained in sx_t and sy_t, each of them with their own sampling rate, and the powerband timecourse of the former source

can be obtained from sx_power.

Finally, the simulated data can be fed into a small preprocessing step, where each dataset and source is standardized (zero mean and unit variance) and split into train and test sets.

[4]:

# Configuration dictionary for the simulation

# (equivalently, can be loaded from a YAML file)

config_dict = {

"Ny": 28, # Number of channels

"Nx": 32,

"Ns_all": 100, # Total number of sources

"Ns_target": 1, # Number of target sources

"T": 300, # Total simulation time (s)

"T_epoch": 0.1, # Length of epochs / Y sampling interval (s)

"rate": 100, # Sampling rate (Hz)

"f_min": 8, # Frequency band (Hz)

"f_max": 12,

"dT": 0, # Time lag between target sources

"invert_sy": False, # Invert sy target source

"gamma_e": 0.5, # Noise strenght factor

"gamma": 0.6, # SNR parameter

"ellx": 0.5, # Width of RBF

"elly": 0.2,

"sigma_noise": 0.1, # RBF white noise strength

}

# Create a simulation object with the configuration dictionary

sim = BimodalToyDataSimulation(config_dict, seed=137, mixing_type="structured")

SNR = 20 * np.log10(sim.args.gamma) # Calculate SNR in dB

print(f"SNR: {SNR:.2f}")

# Plot target sources, channels, and mixing patterns (set xlim for better visualization)

sim.plot_targets(xlim=(0, 30))

sim.plot_channels(N=2, xlim=(0, 30))

sim.plot_mixing_patterns()

# Run small preprocessing step to standardize and split data into train and test sets

train_test_split = 0.8 # Proportion of data to use for training

preprocess_data_dict = sim.preprocess_data(train_test_split)

x_train, x_test = preprocess_data_dict["x_train"], preprocess_data_dict["x_test"]

x_power_train, x_power_test = (

preprocess_data_dict["x_power_train"],

preprocess_data_dict["x_power_test"],

)

y_train, y_test = preprocess_data_dict["y_train"], preprocess_data_dict["y_test"]

sx, sx_power, sy = (

preprocess_data_dict["sx"],

preprocess_data_dict["sx_power"],

preprocess_data_dict["sy"],

)

Random seed set as 137

Simulating sources...

Finished

SNR: -4.44

Regularized CCA

Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) looks for linear projections that maximize the correlation between two datasets \(X\) and \(Y\). In certain scenarios, such as when dealing with high-dimensionality problems (more features than samples) or co-linearities between observations, or when looking for sparse or smooth solutions, regularized CCA is expected to achieve a better performance on the source reconstruction task and help with interpretability. Some of the most well-established regularization/penalty terms are the L1-norm, leading to Sparse CCA, the L2-norm, leading to Ridge CCA, and their combination, known as ElasticNet CCA.

All these methods can be found as classes in the cca_models module inside the multimodal package: CCA, SparseCCA, RidgeCCA, and ElasticNetCCA. The latter contains the first three models as particular cases, so each of them can be also instantiated by picking specific values of the regularization parameters in the ElasticNetCCA class. Its implementation is based on [Parkhomenki et al. 2009].

We now show example use cases of these classes utilizing the toy-model fNIRS-EEG data simulated above. To this end, we will use the bandpower timecourse of \(x\) as one of the inputs, and the timecourse of \(y\) as the second one, both sharing the same sampling rate. The reason behind this choice is that, from a neuroscientific perspective, we expect these quantities to co-modulate, rather than their directy timecourses.

[5]:

from cedalion.sigdecomp.multimodal.cca import (

CCA,

ElasticNetCCA,

RidgeCCA,

SparseCCA,

StructuredSparseCCA,

)

CCA

We have four optional parameters when initializing CCA: N_components is the number of components to extract. If None, the number of components is set to the minimum number of features between modalities. max_iter refers to the maximum number of iterations for the algorithm and tol regulates the tolerance for convergence by checking the norm of the difference between successive vector solutions during iteration. scale (bool) determines whether to scale the data during

normalization to unit variance or just center it.

[6]:

# Initialize model

cca = CCA(N_components=1, max_iter=1000, tol=1e-6, scale=True)

We can now fit the model to some (x_train, y_train). Each of the input datasets need to be an xr.DataArray object with exactly two dimensions: one for features and the other one for samples. Both x and y datasets need to share the same sample dimension name and shape, while features can be different. The dimension naming can be specified with optional parameters. By default, the sample dimension is expected to be named ‘time’ and the feature dimensions ‘channel’.

[7]:

# Fit model

cca.fit(

x_power_train,

y_train,

sample_name="time",

featureX_name="channel",

featureY_name="channel",

)

display(cca.Wx)

<xarray.DataArray (channel: 32, CCA_X: 1)> Size: 256B 0.02794 0.1259 0.04475 0.174 0.03087 ... 0.008922 0.02993 0.2225 -0.002854 Coordinates: * channel (channel) <U3 384B 'X1' 'X2' 'X3' 'X4' ... 'X29' 'X30' 'X31' 'X32' * CCA_X (CCA_X) <U3 12B 'Sx1'

The learned filters, available via cca.Wx, and cca.Wy, can be used to transform a different pair (x_test, y_test). This test set must have the exact same feature dimension (name and shape) as the train data. The sample dimension should be the same between x_test and y_test, and its name must coincide with the one used during training. The number of samples, however, can be different between train and test sets.

[8]:

# Transform data

sx_power_cca, sy_cca = cca.transform(x_power_test, y_test)

print(f"Latent space dimensions: {cca.latent_featureX_name, cca.latent_featureY_name}")

sx_power_cca

Latent space dimensions: ('CCA_X', 'CCA_Y')

[8]:

<xarray.DataArray (time: 600, CCA_X: 1)> Size: 5kB -0.2433 0.1107 0.5429 2.071 1.619 0.1281 ... 2.217 1.67 2.113 1.802 1.129 0.6403 Coordinates: * time (time) float64 5kB 240.1 240.2 240.3 240.4 ... 299.8 299.9 300.0 * CCA_X (CCA_X) <U3 12B 'Sx1'

The transform method returns the “reconstructed sources”, with the same sample dimension as the test input but with a new “latent_feature” dimension, generated automatically from the class/model name.

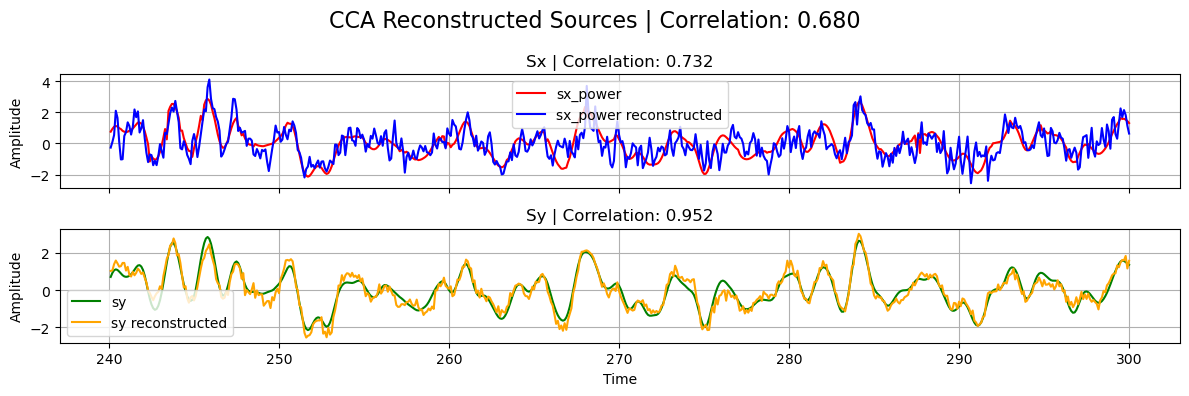

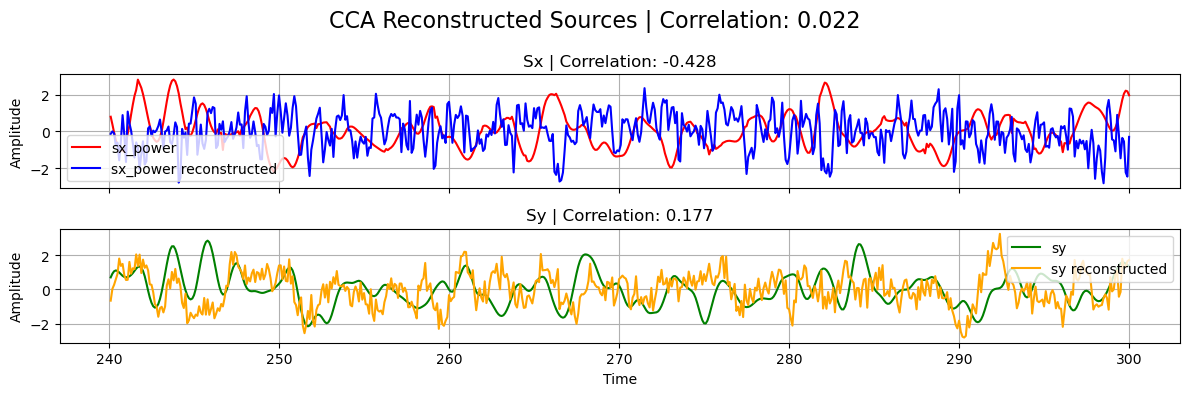

If the decomposition was performed successfully, the reconstructed sources should be close to the ground truth ones used in the linear forward model of the simulated data.

[9]:

# Normalize

sx_power_cca = standardize(sx_power_cca).T

sy_cca = standardize(sy_cca).T

# Calculate correlations

corrxy = np.corrcoef(sx_power_cca[0], sy_cca[0])[0, 1]

corrx = np.corrcoef(sx_power_cca[0], sx_power[0])[0, 1]

corry = np.corrcoef(sy_cca[0], sy[0])[0, 1]

# Plot results

plot_source_comparisson(

sx_power[0], sy[0], sx_power_cca[0], sy_cca[0], corrx, corry, corrxy, title="CCA"

)

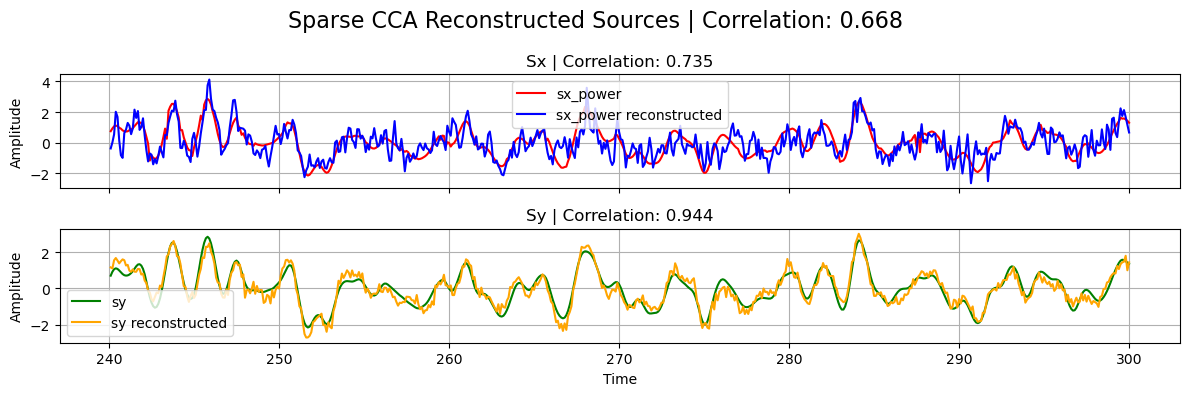

Sparse CCA, Ridge CCA, and ElasticNet CCA

ElasticNetCCA admits the same optional parameters as CCA on top of l1_reg and l2_reg to encode the regularization parameteres for the L1 and L2 penalty terms, respectively. These parameters take a list of the form \([ \lambda_x, \lambda_y]\), containing the regularization parameters for \(W_x\), and \(W_y\), respectively. If, instead, a float \(\lambda\) is passed, then \(\lambda_x=\lambda_y=\lambda\). L1 and L2 parameters need to be non-negative, with

zero-values corresponding to no regularization. Additionally, l1_reg components must be smaller than \(0.5\), while l2_reg components are unbounded. SparseCCA is a sub-class of ElasticNetCCA, obtained by setting l2_reg=0 on the latter. Analogously, RidgeCCA is equivalent to ElasticNetCCA with l1_reg=0. By choosing both regularizers to be zero, we recover the same CCA implementation we explored above.

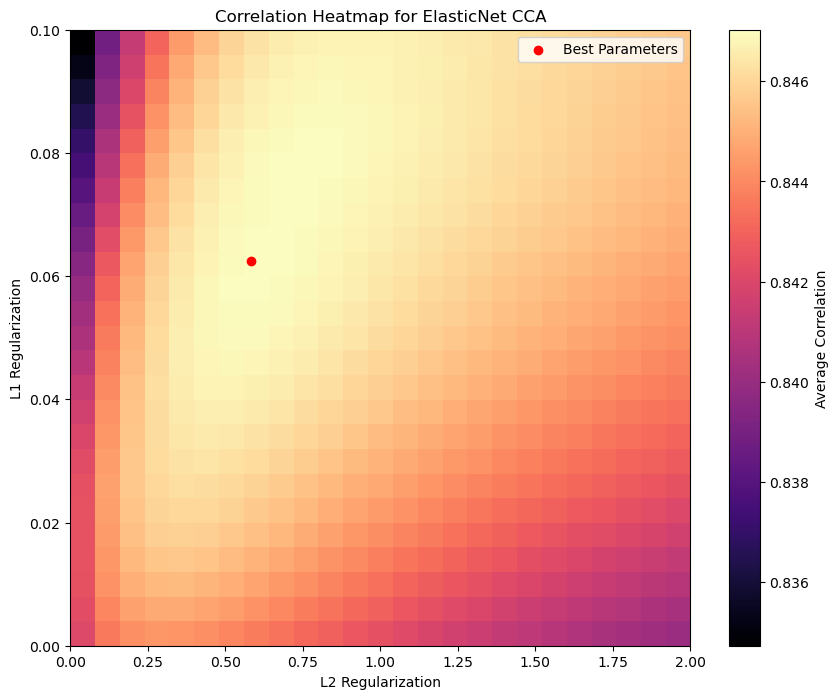

With these regularized methods we can achieve better performance compared to standard CCA, even in lower SNR scenarios, as long as we make the right choice of hyperparamters. The latter gives us more flexibility, but requires a bit of extra work to achieve the optimal model’s performance. For such a hyperparameter exploration, for instance, one can run a small random or grid search together with cross-validation in a validation set.

For the sake of simplicity, we won’t follow that approach here, but rather show how the performance of ElasticNetCCA on the test set varies with different hyperparameter configurations. In particular, by looking at the l1_reg=_l2_reg=0 in parameter space, we can see the increase in performance compared with CCA.

[10]:

# Define ranges for L1 and L2 parameters

l1_reg_list = np.linspace(0, 0.1, 25)

l2_reg_list = np.linspace(0, 2, 25)

# Initialize a list to store correlations regularization parameters

correlations_list = np.zeros((len(l1_reg_list), len(l1_reg_list), 3))

# Loop through parameters

for i, l1 in enumerate(l1_reg_list):

for j, l2 in enumerate(l2_reg_list):

# Initialize (default names for sample and feature dimensions

# is 'time' and 'channel')

elastic_cca = ElasticNetCCA(

N_components=1,

l1_reg=[l1, l1], # L1 regularization parameter (same for both datasets)

l2_reg=l2,

) # L2 regularization parameter (same for both datasets)

# Fit model

elastic_cca.fit(x_power_train, y_train)

# Transform data

sx_power_elastic_cca, sy_elastic_cca = elastic_cca.transform(

x_power_test, y_test

)

# Normalize

sx_power_elastic_cca = standardize(sx_power_elastic_cca).T[0]

sy_elastic_cca = standardize(sy_elastic_cca).T[0]

# Calculate correlations

corrxy_elastic = np.corrcoef(sx_power_elastic_cca, sy_elastic_cca)[0, 1]

corrx_elastic = np.corrcoef(sx_power_elastic_cca, sx_power)[0, 1]

corry_elastic = np.corrcoef(sy_elastic_cca, sy)[0, 1]

correlations_list[i, j] = [corrxy_elastic, corrx_elastic, corry_elastic]

# Find (L1, L2) configuration with highest avarage correlation between corrx and corry

corr_avg = np.mean(correlations_list[:, :, 1:], axis=-1)

i, j = np.unravel_index(np.argmax(corr_avg), corr_avg.shape)

max_corrxy, max_corrx, max_corry = correlations_list[i, j]

best_l1_reg = l1_reg_list[i]

best_l2_reg = l2_reg_list[j]

# CCA correlation with L1=L2=0

cca_corr = correlations_list[0, 0, :]

print(

f"Best L1 regularization: {best_l1_reg:.5f}, "

f"Best L2 regularization: {best_l2_reg:.5f}"

)

print(

f"Max correlation: {max_corrxy:.3f}, "

f"Correlation X: {max_corrx:.3f}, "

f"Correlation Y: {max_corry:.3f}"

)

print(

f"CCA correlation (L1=L2=0): {cca_corr[0]:.3f}, "

f"Correlation X: {cca_corr[1]:.3f}, "

f"Correlation Y: {cca_corr[2]:.3f}"

)

# Plot the correlation heatmap

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 8))

plt.imshow(

corr_avg,

cmap="magma",

aspect="auto",

origin="lower",

extent=[l2_reg_list[0], l2_reg_list[-1], l1_reg_list[0], l1_reg_list[-1]],

interpolation="nearest",

)

plt.colorbar(label="Average Correlation")

plt.xlabel("L2 Regularization")

plt.ylabel("L1 Regularization")

plt.title("Correlation Heatmap for ElasticNet CCA")

plt.scatter(best_l2_reg, best_l1_reg, color="red", label="Best Parameters")

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Best L1 regularization: 0.06250, Best L2 regularization: 0.58333

Max correlation: 0.688, Correlation X: 0.738, Correlation Y: 0.956

CCA correlation (L1=L2=0): 0.680, Correlation X: 0.732, Correlation Y: 0.952

For the other regularization models, initializing, fitting and transforming work in the same way:

[11]:

# Initialize models (use optimal parameters found above)

elasticnet_cca = ElasticNetCCA(

N_components=1,

l1_reg=best_l1_reg, # Use optimal L1, L2 found above

l2_reg=best_l2_reg,

)

# Equals ElasticNetCCA with l1_reg=best_l1_reg and l2_reg=0

sparse_cca = SparseCCA(N_components=1, l1_reg=best_l1_reg)

# Equals ElasticNetCCA with l1_reg=0 and l2_reg=best_l2_reg

ridge_cca = RidgeCCA(N_components=1, l2_reg=best_l2_reg)

# Fit models

elasticnet_cca.fit(x_power_train, y_train)

sparse_cca.fit(x_power_train, y_train)

ridge_cca.fit(x_power_train, y_train)

# Transform data

sx_power_elastic, sy_elastic = elasticnet_cca.transform(x_power_test, y_test)

sx_power_sparse, sy_sparse = sparse_cca.transform(x_power_test, y_test)

sx_power_ridge, sy_ridge = ridge_cca.transform(x_power_test, y_test)

# Normalize

sx_power_elastic = standardize(sx_power_elastic).T[0]

sy_elastic = standardize(sy_elastic).T[0]

sx_power_sparse = standardize(sx_power_sparse).T[0]

sy_sparse = standardize(sy_sparse).T[0]

sx_power_ridge = standardize(sx_power_ridge).T[0]

sy_ridge = standardize(sy_ridge).T[0]

# Calculate correlations

corrxy_elastic = np.corrcoef(sx_power_elastic, sy_elastic)[0, 1]

corrx_elastic = np.corrcoef(sx_power_elastic, sx_power)[0, 1]

corry_elastic = np.corrcoef(sy_elastic, sy)[0, 1]

corrxy_sparse = np.corrcoef(sx_power_sparse, sy_sparse)[0, 1]

corrx_sparse = np.corrcoef(sx_power_sparse, sx_power)[0, 1]

corry_sparse = np.corrcoef(sy_sparse, sy)[0, 1]

corrxy_ridge = np.corrcoef(sx_power_ridge, sy_ridge)[0, 1]

corrx_ridge = np.corrcoef(sx_power_ridge, sx_power)[0, 1]

corry_ridge = np.corrcoef(sy_ridge, sy)[0, 1]

# Plot

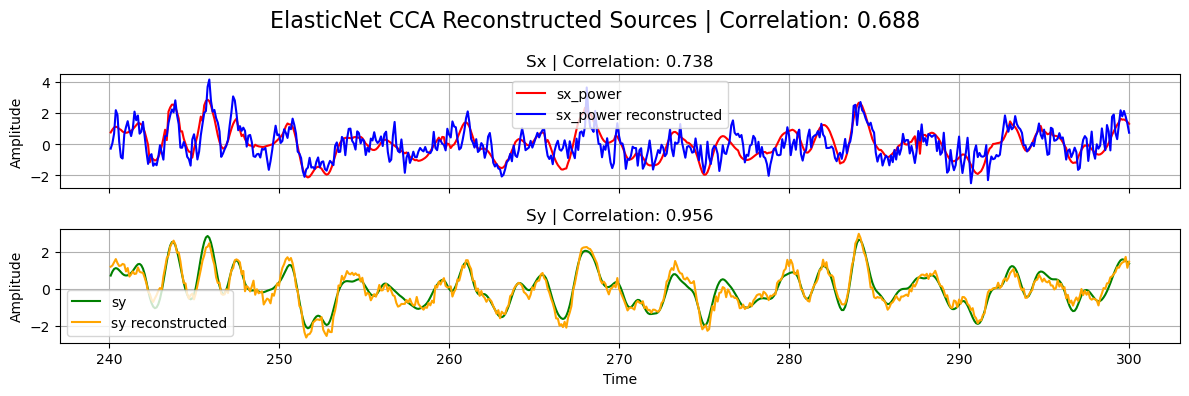

plot_source_comparisson(

sx_power[0],

sy[0],

sx_power_elastic,

sy_elastic,

corrx_elastic,

corry_elastic,

corrxy_elastic,

title="ElasticNet CCA",

)

plot_source_comparisson(

sx_power[0],

sy[0],

sx_power_sparse,

sy_sparse,

corrx_sparse,

corry_sparse,

corrxy_sparse,

title="Sparse CCA",

)

plot_source_comparisson(

sx_power[0],

sy[0],

sx_power_ridge,

sy_ridge,

corrx_ridge,

corry_ridge,

corrxy_ridge,

title="Ridge CCA",

)

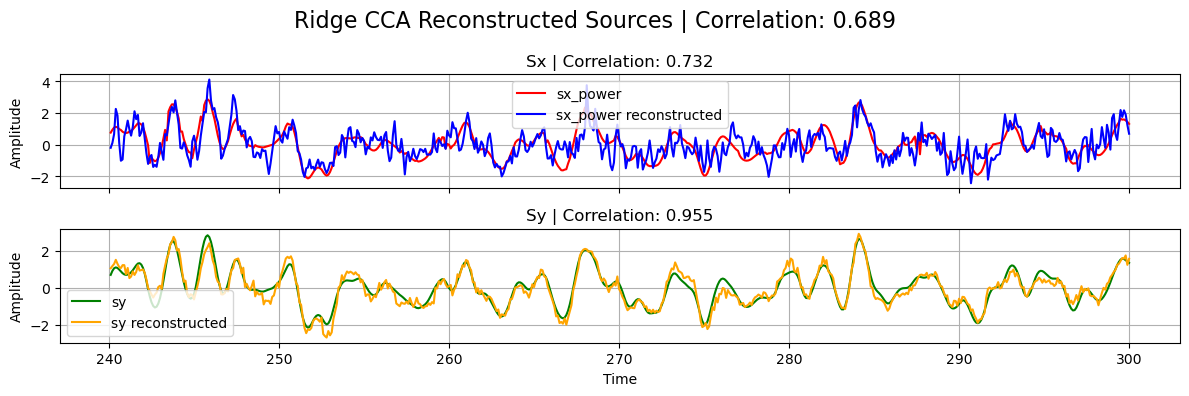

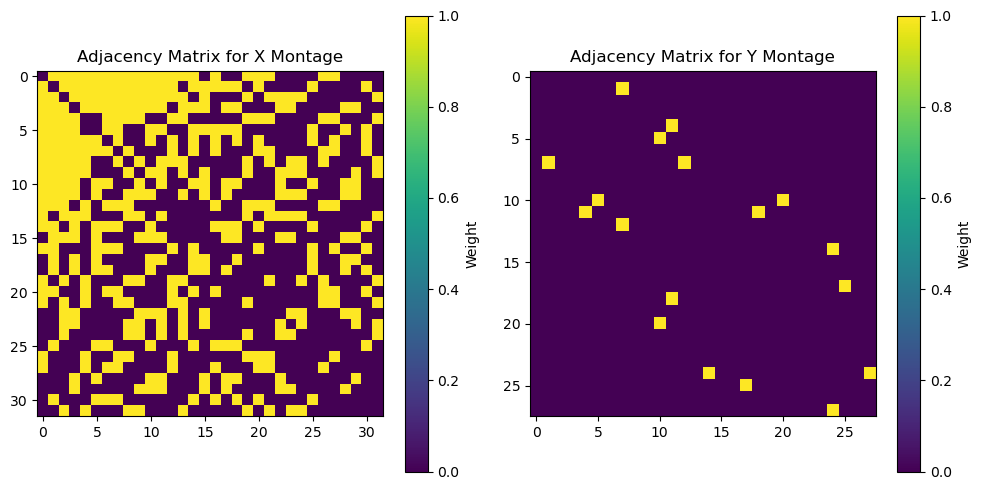

Structured Sparse CCA (ssCCA)

ElasticNet regularization can be modified to include contextual information about the local structure of the dataset, leading to structured CCA. This is particularly relevant in neuroimaging, where features (e.g. channels or brain regions) follow specific spatial distributions. One way of incorporating this prior information is to modify the L2-norm penalty term on the filters \(W\) via \(||W||_2^2 \rightarrow W^T L W\) for some matrix \(L\) that captures the local dependencies among

features. When this structure contraint is combined with an L1 penalization, the resulting method is called structured sparse CCA (ssCCA) and is implemented in Cedalion as the StructuredSparseCCA class, following [Chen et al. 2013].

This class admits the same parameters as ElasticNetCCA together with Lx and Ly, corresponding to structure matrices used for each dataset. The latter need to be square matrices of shapes \((Nx, Nx)\) and \((Ny, Ny)\), in terms of the number of features of each dataset. This time, the l2_reg parameter regulates the strength of the structured penalty term, and must be non-negative but otherwise unbounded.

One popular choice for such structure contraint is the Laplacian matrix, which is used as a graph representation of the dataset, in which features (channels) are the nodes, and (weighted) edges indicate which and how features are connected. We now show a simple example of a Laplacian matrix, build via an adjacency matrix that uses a binary nearest-neighbord strategy.

[12]:

# Helper function to build Laplacian matrix

def build_laplace(nodes, eps):

"""Builds Laplacian matrix of a graph.

The nodes are the components of the 1D vector nodes,

by giving unit weight to connected nodes only if they are close enough.

The latter condition is determined by comparing the 2-norm between nodes and eps.

"""

N = len(nodes)

Adj = np.zeros([N, N]) # Adjacency matrix

D = np.eye(N) # Degree matrix

for i, xi in enumerate(nodes):

for j, xj in enumerate(nodes):

if i == j: # Skip diagonal entries

continue

are_close = np.linalg.norm(xi - xj) < eps

Adj[i, j] = 1 if are_close else 0

D[i, i] = np.sum(Adj[i])

L = D - Adj # Laplace matrix

return L, Adj

[13]:

# Read channel positions from simulation

x_channels_pos = sim.x_montage.values

y_channels_pos = sim.y_montage.values

# Build Laplacian matrix from each montage

# (eps thresholds chosen by small experimentation)

Lx, Adjx = build_laplace(x_channels_pos, eps=sim.args.ellx)

Ly, Adjy = build_laplace(y_channels_pos, eps=sim.args.elly)

# Plot Adjacency matrices

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 5))

plt.subplot(1, 2, 1)

plt.imshow(Adjx, cmap="viridis", interpolation="nearest")

plt.title("Adjacency Matrix for X Montage")

plt.colorbar(label="Weight")

plt.subplot(1, 2, 2)

plt.imshow(Adjy, cmap="viridis", interpolation="nearest")

plt.title("Adjacency Matrix for Y Montage")

plt.colorbar(label="Weight")

plt.tight_layout()

The choice of structure/Laplace matrix introduces yet another layer of complexity to the model, which needs further fine-tunning to achieve its optimal performance. Since making an exhaustive investigation is beyond the scope of this tutorial notebook, here we just chose the nearest-neighbor thresholds to coincide with the ground truth RBF width used in the simulated mixing matrices, and picked the same regularization parameters as for ElasticNetCCA above. Initialization, fitting, and

transformation follows the same logic as before:

[14]:

sscca = StructuredSparseCCA(

N_components=1,

l1_reg=best_l1_reg, # Use optimal L1, L2 found above

l2_reg=best_l2_reg,

Lx=Lx, # Laplacian matrix for X montage

Ly=Ly, # Laplacian matrix for Y montage

)

# Fit model

sscca.fit(x_power_train, y_train)

# Transform data

sx_power_sscca, sy_sscca = sscca.transform(x_power_test, y_test)

# Normalize

sx_power_sscca = standardize(sx_power_sscca).T[0]

sy_sscca = standardize(sy_sscca).T[0]

# Calculate correlations

corrxy_sscca = np.corrcoef(sx_power_sscca, sy_sscca)[0, 1]

corrx_sscca = np.corrcoef(sx_power_sscca, sx_power)[0, 1]

corry_sscca = np.corrcoef(sy_sscca, sy)[0, 1]

# Plot

plot_source_comparisson(

sx_power[0],

sy[0],

sx_power_sscca,

sy_sscca,

corrx_sscca,

corry_sscca,

corrxy_sscca,

title="Structured Sparse CCA",

)

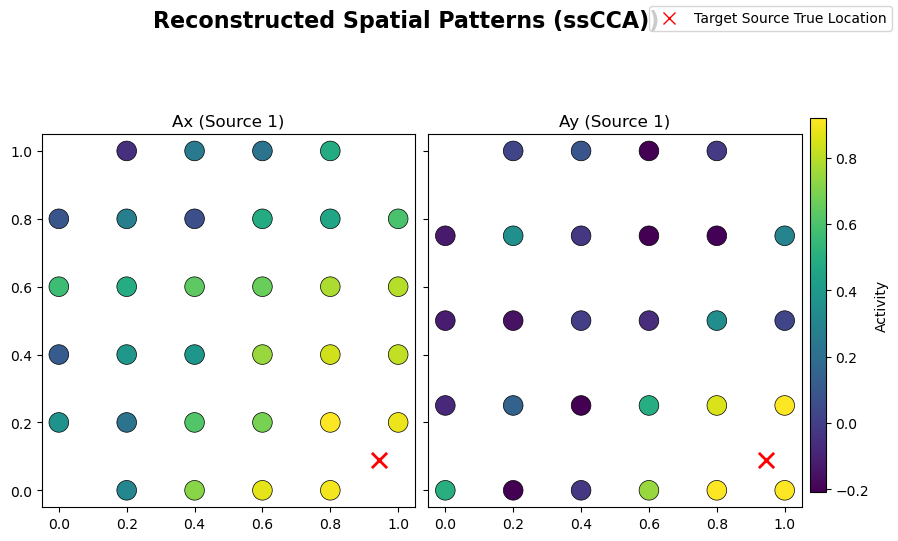

From the learned weights, Wx and Wy, one can estimate the spattial patterns Ax and Ay via a regression method [Haufe et al. 2014]. These quantities should be close to the original mixing matrices used in the linear forward model of the simulated data. Structured regularization is particularly promising for such a reconstruction task given the incorporation of spatial information during the

decomposition:

[15]:

# Helper function to estimate spatial patterns from

# learned weights via regression approach

def compute_spatial_pattern_from_weight(

X_xr, W_xr, sample_name="time", feature_name="channel"

):

# Bring to standard order

X_xr = X_xr.transpose(sample_name, feature_name)

W_xr = W_xr.transpose(feature_name, ...)

# Work with numpy arrays from now on

N = len(X_xr[sample_name])

X = X_xr.data

W = W_xr.data

# Covariance matrix for X

C = (X.T @ X) / (N - 1)

# Covariance matrix for reconstructed sources

Cs = W.T @ C @ W

# Estimated spattial pattern

A = C @ W @ sp.linalg.pinv(Cs)

# Bring to DataArray format\

A = xr.DataArray(A, dims=W_xr.dims, coords=W_xr.coords)

return A

# Compute spatial patterns from learned weights for ssCCA

Ax_sscca = compute_spatial_pattern_from_weight(x_test, sscca.Wx)

Ay_sscca = compute_spatial_pattern_from_weight(y_test, sscca.Wy)

# Normalize

Ax_sscca /= Ax_sscca.max()

Ay_sscca /= Ay_sscca.max()

# Plot original mixing patterns

sim.plot_mixing_patterns(title="Original Mixing Patterns")

# Plot estimated spatial patterns

sim.plot_mixing_patterns(

Ax=Ax_sscca.values,

Ay=Ay_sscca.values,

title="Reconstructed Spatial Patterns (ssCCA))",

)

Additional Functionalities

Apart from the functionalities already covered for the regularized and standard CCA implementations, there are few addtional features that are worth mentioning. Given their usage are rather straightforward, we leave the exploration to the curious reader.

Multiple Components

So far we just covered the one-unit algorithms, i.e. we extracted only one component/source. As mentioned above, all these methods can be used to extract several components by changing the value of the N_component parameter. That value cannot be bigger than the minimum between the number of X and Y features. The way these extra components are extracted is by following a deflation approach, where at each iteration the contribution from the previous component is removed from the input matrix

entering the decomposition.

[16]:

# Example case of multiple components CCA

cca_multiple_comp = CCA(N_components=10)

cca_multiple_comp.fit(x_power_train, y_train)

display(cca_multiple_comp.Wy)

<xarray.DataArray (channel: 28, CCA_Y: 10)> Size: 2kB 0.009316 -0.04114 0.3194 -0.1812 -0.2955 ... -0.5022 -0.1405 -0.474 0.02501 Coordinates: * channel (channel) <U3 336B 'Y1' 'Y2' 'Y3' 'Y4' ... 'Y25' 'Y26' 'Y27' 'Y28' * CCA_Y (CCA_Y) <U4 160B 'Sy1' 'Sy2' 'Sy3' 'Sy4' ... 'Sy8' 'Sy9' 'Sy10'

Partial Least Squares (PLS)

PLS is a multimodal source-decomposition algorithm very similar to CCA. The latter maximizes correlation between the projected views, while PLS maximizes covariance. From a practical point of view, PLS can be obtained from CCA by sending the covariance matrices \(C_x\) and \(C_y\) to the identity matrices in the cost function. Therefore, both algorithms coincide when the input datasets are whitened.

Within Cedalion, we can use these methods via the classes PLS, and SparsePLS [Witten et al. 2009]. The Ridge version of PLS simply does not exist, because PLS itself can be understood as an extreme case of RidgeCCA where \(\lambda_2 \to \infty\). Internally, the classes are obtained from ElasticNetCCA with the extra parameter pls=True.

[17]:

from cedalion.sigdecomp.multimodal.cca import PLS, SparsePLS

[18]:

# Example initialization of PLS and SparsePLS models

pls = PLS(N_components=1, max_iter=1000, tol=1e-6, scale=True)

sparse_pls = SparsePLS(N_components=1, l1_reg=[0.1, 0.01])

Temporally Embedded CCA (tCCA)

The methods covered so far assume modalities correlate instantaneously, which is certainly not the case in fNIRS-EEG fusion, for instance, where the common underlying sources are time-shifted due to hemodynamic delays. Temporally embedded CCA (tCCA) [Biessmann et al., 2010] captures such temporal offsets. While effective, the idea is rather simple: assuming \(y\) is the ”delayed” modality, \(x\) is time-embedded by concatenating time-shifted copies along the feature dimension, leading to a time-embedded dataset \(\tilde{x}\). The time lags must be preselected, introducing a new parameter to the model. Standard CCA (or any of the variants explored above) is then applied without further modifications on (\(\tilde{x}\), \(y\)), yielding temporal filters that capture delayed correlations between modalities.

All the CCA variants covered above admit a temporally embedded extension, and they are implemented in Cedalion in the tcca_models module, which contains the classes tCCA, ElasticNetTCCA, and StructuredSparseTCCA. Analogously to the simultaneuously-coupled models, Sparse tCCA and Ridge tCCA can be obtained from ElasticNetTCCA by the right choice of l1_reg and l2_reg parameters, but in this case they do not have their own classes.

[19]:

from cedalion.sigdecomp.multimodal.tcca import (

tCCA,

# ElasticNetTCCA,

# StructuredSparseTCCA,

)

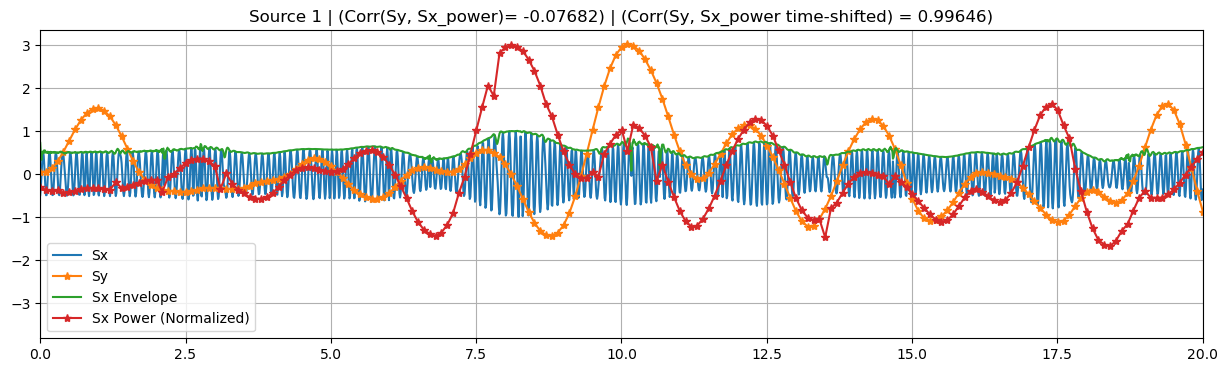

In order to show how these models are used, let’s build a time-shifted version of the simulated data from above:

[20]:

# Use the same configuration dictionary as before but with a non-zero time lag

config_dict["dT"] = 2 # Time lag between target sources (s)

# Simulate

sim = BimodalToyDataSimulation(config_dict, seed=137, mixing_type="structured")

SNR = 20 * np.log10(sim.args.gamma) # Calculate SNR in dB

print(f"SNR: {SNR:.2f}")

print("Time lag between target sources:", sim.args.dT, "s")

# Plot target sourcers, channels, and mixing patterns

# (add xlim now to see the effect of time lag)

sim.plot_targets(xlim=(0, 20))

# sim.plot_channels(N=2)

# sim.plot_mixing_patterns()

# Run small preprocessing step to standardize and

# split the data into train and test sets

train_test_split = 0.8 # Proportion of data to use for training

preprocess_data_dict = sim.preprocess_data(train_test_split)

x_train, x_test = preprocess_data_dict["x_train"], preprocess_data_dict["x_test"]

x_power_train, x_power_test = (

preprocess_data_dict["x_power_train"],

preprocess_data_dict["x_power_test"],

)

y_train, y_test = preprocess_data_dict["y_train"], preprocess_data_dict["y_test"]

sx, sx_power, sy = (

preprocess_data_dict["sx"],

preprocess_data_dict["sx_power"],

preprocess_data_dict["sy"],

)

Random seed set as 137

Simulating sources...

Finished

SNR: -4.44

Time lag between target sources: 2 s

These time-embedded classes are built on top of their simultaneuously-coupled counterparts, sharing several attributes and methods. In particular, they accept the same parameters as before, in addition to time_shifts and shift_source.

The former must be a Numpy array, containing the time-lags to be applied to the \(x\) modality. These lags should be non-negative float numbers within the time domain of the data. Because of the latter, a validation/consistency check of this array is carried only after fitting the model. During that validation, a time-lag \(= 0\) component would be added to time_shift if not present already (zero-lag \(x\) copy), and the resulting array is sorted in ascending order.

If the shift_source parameter is set to True, the reconstructed source \(s_x\), obtained after transforming the data, is shifted by an optimal_shift, so it is temporally aligned with the reconstructed source \(s_y\). This optimal shift attribute is estimated right after training by looking for the time-shifted x that produces the biggest correlation between reconstructed sources \(s_x\) and \(s_y\). Note that the optimal_shift attribute is available even when

shift_source=False, so one can apply the shift a posteri if desired. It is worth clarifying that this shift is only estimated using the (train) data used during fitting.

[21]:

# Temporal embedding parameters

dt = 1

N_lags = 5

time_shifts = np.arange(0, dt * N_lags, dt)

print(f"Time shifts: {time_shifts}")

print("True time lag between target sources:", sim.args.dT, "s")

# Initialize tCCA model

tcca = tCCA(

N_components=1,

max_iter=1000,

tol=1e-6,

scale=True,

time_shifts=time_shifts,

shift_source=True,

)

Time shifts: [0 1 2 3 4]

True time lag between target sources: 2 s

Fitting works in the same way as before, except that sample_name is assumed always to be time.

[22]:

# Fit model

tcca.fit(x_power_train, y_train, featureX_name="channel", featureY_name="channel")

# At this point we have an estimate for the time lag between target sources

print(

f"Estimated time lag between target sources "

f"during training: {tcca.optimal_shift[0]} s"

)

display(tcca.Wx)

Estimated time lag between target sources during training: 2.0 s

<xarray.DataArray (time_shift: 5, channel: 32, tCCA_X: 1)> Size: 1kB 0.00386 0.002902 0.01951 -0.01833 -0.0143 ... 0.03439 0.01409 0.003379 0.05622 Coordinates: * time_shift (time_shift) int64 40B 0 1 2 3 4 * channel (channel) <U3 384B 'X1' 'X2' 'X3' 'X4' ... 'X30' 'X31' 'X32' * tCCA_X (tCCA_X) <U3 12B 'Sx1'

The learned weights Wx now have an extra time_shift dimension, where each component contains the filters applied to the copy of \(x\) shifted by that particular time-lag. Wy remains with the same shape as previous models.

Data transformation is also applied in the same manner, but in this case, if shift_sources=True, the reconstructed sources are truncated by removing the last optimal shift seconds, containing null values introduced by the zero-padding used during shifting.

[23]:

# Transform data

sx_power_tcca, sy_tcca = tcca.transform(x_power_test, y_test)

display(sx_power_tcca, sx_power)

<xarray.DataArray (time: 580, tCCA_X: 1)> Size: 5kB 2.014 0.707 0.3418 0.8845 -0.2528 ... -0.06712 -0.4116 0.5565 0.4488 0.2566 Coordinates: * time (time) float64 5kB 240.1 240.2 240.3 240.4 ... 297.8 297.9 298.0 * tCCA_X (tCCA_X) <U3 12B 'Sx1'

<xarray.DataArray (source: 1, time: 600)> Size: 5kB 0.8019 0.3854 -0.06178 -0.4672 -0.7737 -0.9842 ... 1.732 2.067 2.226 2.188 1.977 Coordinates: * time (time) float64 5kB 240.1 240.2 240.3 240.4 ... 299.8 299.9 300.0 * source (source) <U2 8B 'S1'

Because of this sample number mismatch with the ground truth sources, we need to truncate the latter before any comparisson:

[24]:

# Normalize

sx_power_tcca = standardize(sx_power_tcca).T[0]

sy_tcca = standardize(sy_tcca).T[0]

# Truncate ground truth sources to match the reconstructed sources

if len(sx_power_tcca) < len(sx_power.time):

sx_power_trunc = sx_power[0, : len(sx_power_tcca)]

if len(sy_tcca) < len(sy.time):

sy_trunc = sy[0, : len(sy_tcca)]

# Calculate correlations. Should be low because sx is shifted!

corrxy_tcca = np.corrcoef(sx_power_tcca, sy_tcca)[0, 1]

corrx_tcca = np.corrcoef(sx_power_tcca, sx_power_trunc)[0, 1]

corry_tcca = np.corrcoef(sy_tcca, sy_trunc)[0, 1]

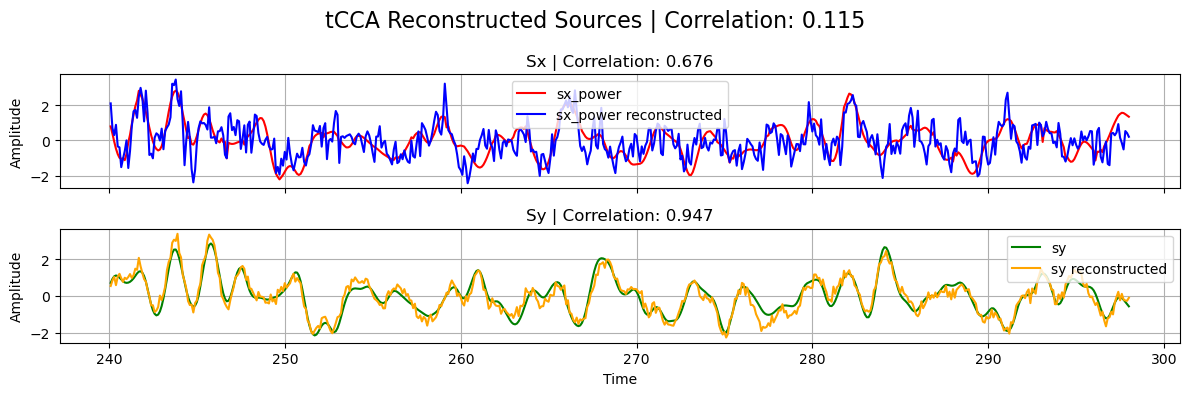

We also train a standard CCA method so we can compare and see the importance of capturing the time lags in the data:

[25]:

# CCA

cca = CCA(N_components=1)

cca.fit(x_power_train, y_train)

sx_cca, sy_cca = cca.transform(x_power_test, y_test)

# Normalize

sx_cca = standardize(sx_cca).T[0]

sy_cca = standardize(sy_cca).T[0]

# Calculate correlations for CCA

corrxy_cca = np.corrcoef(sx_cca, sy_cca)[0, 1]

corrx_cca = np.corrcoef(sx_cca, sx_power)[0, 1]

corry_cca = np.corrcoef(sy_cca, sy)[0, 1]

[26]:

# Plot results

plot_source_comparisson(

sx_power_trunc,

sy_trunc,

sx_power_tcca,

sy_tcca,

corrx_tcca,

corry_tcca,

corrxy_tcca,

title="tCCA",

)

plot_source_comparisson(

sx_power[0], sy[0], sx_cca, sy_cca, corrx_cca, corry_cca, corrxy_cca, title="CCA"

)

Note that, in the previous plot, the correlation between the reconstructed sources from tCCA is naturally low since \(s_x\) has been shifted with the estimated optimal_shift.

Aditional Functionalities

As for the regularized CCA classes, the temporally-embedded extensions can also extract multiple components (using the same deflation algorithm), and the PLS variant can be used by settting pls=True during initialization.

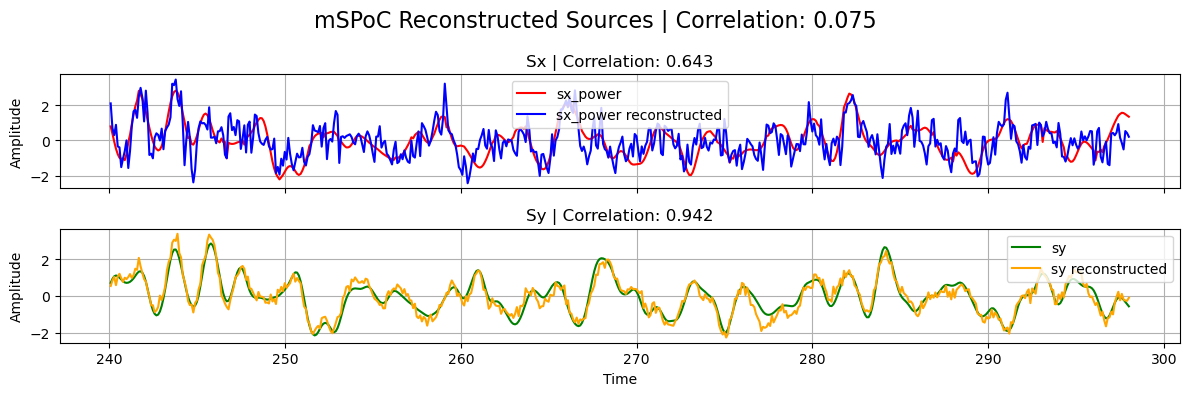

Multimodal Source Power Co-modulation (mSPoC)

EEG bandpower and hemodynamic responses captured by fNIRS are proven to comodulate during cognitive tasks. Conventional methods, such as CCA and its variants, however, present some limitations to integrate bandpower signals. More precisely, computing bandpower at channel level and then applying a backward linear method, as we have been doing so far, is not in line with the assumed linear generative model of EEG. mSPoC [Dähne, et.al. 2013] arises

as a method that avoids these pitfalls by inverting the generative model prior to computing bandpower, and is implemented in Cedalion as the mSPoC class inside the mspoc module.

The algorithm takes two vector-valued time series \(x(t)\), and \(y(e)\), which are time-aligned but have different sample dimensions Ntx > Nty. It is expected that \(x(t)\) has been previously bandpassed filtered to the band of interest. It finds components \(s_x(t)\) and \(s_y(e)\) via linear projection of the observations, such that the covariance between the temporally-embedded,bandpower of \(s_x(t)\) and the time course of \(s_y(e)\) is maximized. The

bandpower of \(s_x(t)\) is estimated by dividing the source into non-overlapping time windows (or epochs), such that there is one window per data point \(y(e)\), and computing the variance within epochs. After such operation, both signals share the same sampling rate and their cross-covariance can be calculated. The solution to the optimization problem is captured by the spatial (Wx, Wy), and temporal (Wt) filters.

[27]:

from cedalion.sigdecomp.multimodal.mspoc import mSPoC

The mSPoC class accepts the very same parameters as the tCCA class, namely N_components, max_iter, tol, scale, time_shifts, and shift_source, with the addition of N_restarts. The latter determines the number of times the algorithm is repeated, which may find better extrema in the optimization problem, due to its stochastic nature. Typical values for N_restarts lie between 2 and 10, and it is recommended to choose smaller max_iter and bigger tol

values, compared to simpler CCA methods, due the increased computational time required in mSPoC. As all previous CCA-based methods, mSPoC can also extract multiple components.

[28]:

# We run the same simulation as for tCCA above

config_dict["dT"] = 2

sim = BimodalToyDataSimulation(config_dict, seed=137, mixing_type="structured")

SNR = 20 * np.log10(sim.args.gamma) # Calculate SNR in dB

print(f"SNR: {SNR:.2f}")

print("Time lag between target sources:", sim.args.dT, "s")

sim.plot_targets(xlim=(0, 20))

# Run small preprocessing step to standardize and

# split the data into train and test sets

train_test_split = 0.8

preprocess_data_dict = sim.preprocess_data(train_test_split)

x_train, x_test = preprocess_data_dict["x_train"], preprocess_data_dict["x_test"]

x_power_train, x_power_test = (

preprocess_data_dict["x_power_train"],

preprocess_data_dict["x_power_test"],

)

y_train, y_test = preprocess_data_dict["y_train"], preprocess_data_dict["y_test"]

sx, sx_power, sy = (

preprocess_data_dict["sx"],

preprocess_data_dict["sx_power"],

preprocess_data_dict["sy"],

)

# Temporal embedding parameters (same as for tCCA)

dt = 1

N_lags = 5

time_shifts = np.arange(0, dt * N_lags, dt)

print(f"Time shifts: {time_shifts}")

print("True time lag between target sources:", sim.args.dT, "s")

# Initialize mSPoC model

mspoc = mSPoC(

N_components=1,

N_restarts=2,

max_iter=100, # Note we use much smaller values than before

tol=1e-4,

scale=True,

time_shifts=time_shifts,

shift_source=True,

)

Random seed set as 137

Simulating sources...

Finished

SNR: -4.44

Time lag between target sources: 2 s

Time shifts: [0 1 2 3 4]

True time lag between target sources: 2 s

Fit and transform work analogously to the tCCA method, except that this time the number of samples in the \(x\) input should be bigger than the number of \(y\) samples.

[29]:

# Fit model (sample_name fixed to be 'time' in mSPoC)

mspoc.fit(

x_train,

y_train, # Note that we use x_train here, not x_power_train

featureX_name="channel",

featureY_name="channel",

)

# At this point we have an estimate for the time lag between target sources

print(

"Estimated time lag between target sources "

f"during training: {mspoc.optimal_shift[0]} s"

)

# Learned filters

display(mspoc.Wx)

display(mspoc.Wt)

Estimated time lag between target sources during training: 2 s

<xarray.DataArray (channel: 32, mSPoC_X: 1)> Size: 256B 0.009032 -0.02669 0.05469 -0.04415 -0.02208 ... -0.1543 -0.05827 -0.1278 -0.0265 Coordinates: * channel (channel) <U3 384B 'X1' 'X2' 'X3' 'X4' ... 'X29' 'X30' 'X31' 'X32' * mSPoC_X (mSPoC_X) <U3 12B 'Sx1'

<xarray.DataArray (time_embedding: 5, mSPoC_T: 1)> Size: 40B -0.06374 -0.0625 0.991 -0.08447 -0.05272 Coordinates: * time_embedding (time_embedding) int64 40B 0 1 2 3 4 * mSPoC_T (mSPoC_T) <U3 12B 'St1'

The reconstructed sources returned by transform correspond to the temporally-embedded bandpower of the source \(s_x\), and the time course of \(s_y\). Because of this choice, the outputs are directly comparable, since they have the same sampling time. As before, whenever shift_source=True, the time dimensions of the sources are truncated, removing the last optimal_shift seconds.

[30]:

# Transform data

sx_power_mspoc, sy_mspoc = mspoc.transform(x_test, y_test)

display(sx_power_mspoc, sx_power)

display(sy_mspoc, sy)

# Normalize

sx_power_mspoc = standardize(sx_power_mspoc).T[0]

sy_mspoc = standardize(sy_mspoc).T[0]

<xarray.DataArray (time: 580, mSPoC_X: 1)> Size: 5kB 0.9518 0.8879 0.838 1.385 1.158 1.05 ... 0.8189 0.9737 0.626 1.605 2.467 1.912 Coordinates: * time (time) float64 5kB 240.1 240.2 240.3 240.4 ... 297.8 297.9 298.0 * mSPoC_X (mSPoC_X) <U3 12B 'Sx1'

<xarray.DataArray (source: 1, time: 600)> Size: 5kB 0.8019 0.3854 -0.06178 -0.4672 -0.7737 -0.9842 ... 1.732 2.067 2.226 2.188 1.977 Coordinates: * time (time) float64 5kB 240.1 240.2 240.3 240.4 ... 299.8 299.9 300.0 * source (source) <U2 8B 'S1'

<xarray.DataArray (time: 580, mSPoC_Y: 1)> Size: 5kB 0.6547 1.091 1.502 0.9325 1.586 ... -0.07052 -0.5063 -0.2778 -0.4498 -0.1842 Coordinates: * time (time) float64 5kB 240.1 240.2 240.3 240.4 ... 297.8 297.9 298.0 * mSPoC_Y (mSPoC_Y) <U3 12B 'Sy1'

<xarray.DataArray (source: 1, time: 600)> Size: 5kB 0.7055 0.9216 1.062 1.11 1.077 0.9927 ... 1.532 1.584 1.563 1.5 1.425 1.356 Coordinates: * source (source) <U2 8B 'S1' * time (time) float64 5kB 240.1 240.2 240.3 240.4 ... 299.8 299.9 300.0

As before, we truncate the ground truth sources for a direct comparison

[31]:

# Truncate ground truth sources to match the reconstructed sources

if len(sx_power_mspoc) < len(sx_power.time):

sx_power_trunc = sx_power[0, : len(sx_power_mspoc)]

else:

sx_power_trunc = sx_power[0]

if len(sy_mspoc) < len(sy.time):

sy_trunc = sy[0, : len(sy_mspoc)]

else:

sy_trunc = sy[0]

# Calculate correlations. corrxy_mspoc should be low because sx is shifted!

corrxy_mspoc = np.corrcoef(sx_power_mspoc, sy_mspoc)[0, 1]

corrx_mspoc = np.corrcoef(sx_power_mspoc, sx_power_trunc)[0, 1]

corry_mspoc = np.corrcoef(sy_mspoc, sy_trunc)[0, 1]

# Plot results

plot_source_comparisson(

sx_power_trunc,

sy_trunc,

sx_power_tcca,

sy_tcca,

corrx_mspoc,

corry_mspoc,

corrxy_mspoc,

title="mSPoC",

)

ICA Source Extraction

Source reconstruction in ICA-ERBM is done by minimizing the mutual information rate of the estimated sources. A demixing matrix \(W\) is determined and the estimated sources \(\hat S \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times T }\) can be computed as

Among the extracted sources, we will identify the ones that correspond to the PPG and Mayer Wave signals.

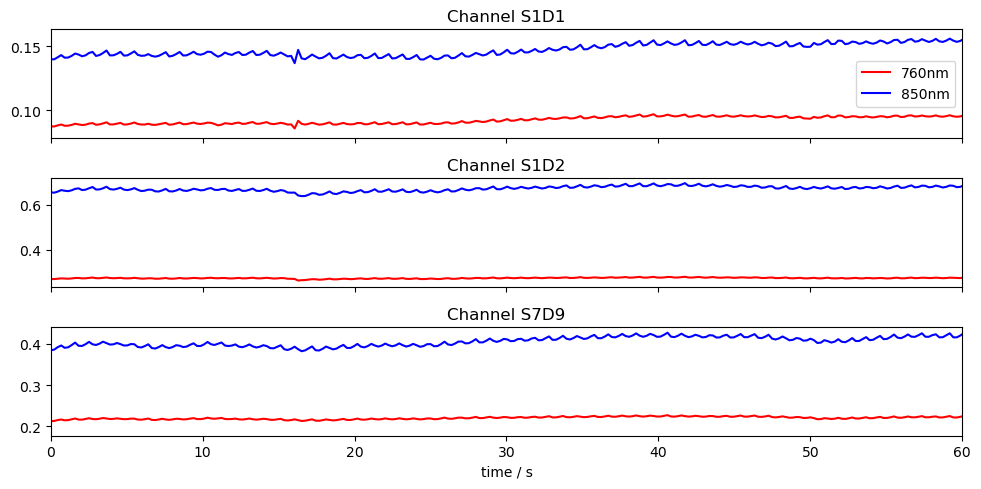

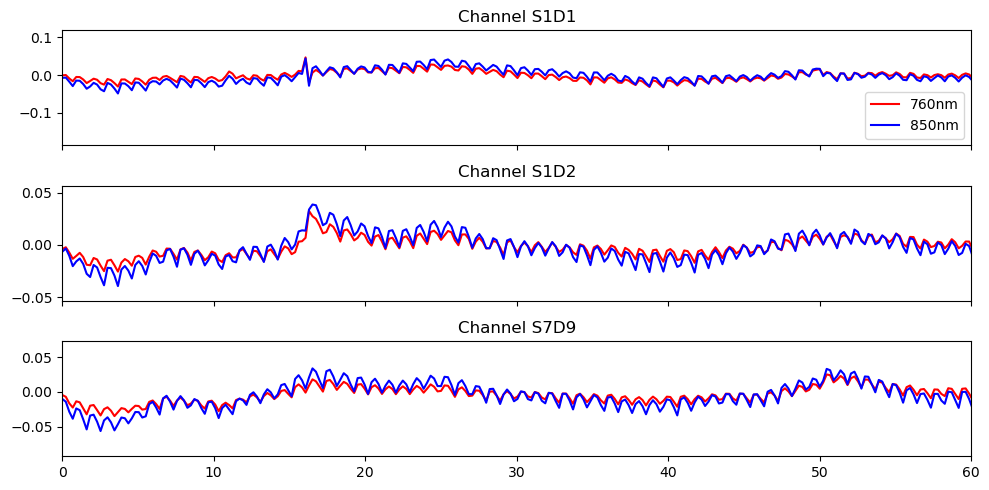

Loading Raw Finger Tapping Data

[32]:

# Load finger tapping data set

finger_tapping_data = cedalion.data.get_fingertappingDOT()

# Extract the fnirs recording

fnirs_data = finger_tapping_data['amp']

# Plot three channels of the fnirs data

fig, ax = plt.subplots(3, 1, sharex=True, figsize=(10, 5))

for i, ch in enumerate(["S1D1", "S1D2", "S7D9"]):

ax[i].plot(fnirs_data.time, fnirs_data.sel(channel=ch, wavelength="760"), "r-", label="760nm")

ax[i].plot(fnirs_data.time, fnirs_data.sel(channel=ch, wavelength="850"), "b-", label="850nm")

ax[i].set_title(f"Channel {ch}")

ax[0].legend()

ax[2].set_xlim(0,60)

ax[2].set_xlabel("time / s")

plt.tight_layout()

Conversion to Optical Density

[33]:

# Convert to Optical Density (OD)

fnirs_data_od = cedalion.nirs.cw.int2od(fnirs_data)

Channel Quality Assessment and Pruning

The Scalp Coupling Index (SCI) and Peak Spectral Power (PSP) are used for quality assessment. We compute SCI and PSP for each channel, and remove channels with less than 75% of clean time.

[34]:

# Calculate masks for SCI and PSP quality metrics

window_length = 5 * units.s

sci_thresh = 0.75

psp_thresh = 0.1

sci_psp_percentage_thresh = 0.75

sci, sci_mask = quality.sci(fnirs_data_od, window_length, sci_thresh)

psp, psp_mask = quality.psp(fnirs_data_od, window_length, psp_thresh)

sci_x_psp_mask = sci_mask & psp_mask

perc_time_clean = sci_x_psp_mask.sum(dim="time") / len(sci.time)

sci_psp_mask = [perc_time_clean >= sci_psp_percentage_thresh]

# Prune channels that do not pass the quality test

fnirs_data_pruned, drop_list = quality.prune_ch(fnirs_data_od, sci_psp_mask, "all")

# Display pruned channels

print(f"List of pruned channels: {drop_list} ({len(drop_list)})")

List of pruned channels: ['S13D26'] (1)

High-pass filter

[35]:

# Filter the data

# fmax = 0 is used to indicate high-pass filtering

fnirs_data_filtered = fnirs_data_pruned.cd.freq_filter(fmin= 0.01, fmax= 0, butter_order=4)

# Store sampling rate

fnirs_data_samplingrate = sampling_rate(fnirs_data_pruned.time).magnitude

# Plot the filtered data

fig, ax = plt.subplots(3, 1, sharex=True, figsize=(10, 5))

for i, ch in enumerate(["S1D1", "S1D2", "S7D9"]):

ax[i].plot(fnirs_data_filtered.time, fnirs_data_filtered.sel(channel=ch, wavelength="760"), "r-", label="760nm")

ax[i].plot(fnirs_data_filtered.time, fnirs_data_filtered.sel(channel=ch, wavelength="850"), "b-", label="850nm")

ax[i].set_title(f"Channel {ch}")

ax[0].legend()

ax[2].set_xlim(0,60)

ax[2].set_label("time / s")

plt.tight_layout()

Select Channels and Time Slice for ICA

The entire finger tapping dataset was recorded over 30 minutes and contains 99 channels after pruning. Unfortunately, these dimensions result in a long runtime for ICA-ERBM. For this reason, we will use only a subset of the channels and a 10-minute slice of the selected channels. Despite the longer runtime, this example is also applicable to the full dataset.

[36]:

# Choose the best 30 channels based on the percentage of time clean

id_best_channels = np.argsort(perc_time_clean).values[-30:]

best_channels = fnirs_data['channel'][id_best_channels]

# Extract the best channels from the filtered data

fnirs_best_channels = fnirs_data_filtered.sel(channel = best_channels)

# Select a 10 min interval

duration = 10 * 60

buffer = 60

fnirs_best_channels = fnirs_best_channels.sel(time=slice(buffer, buffer + duration))

# Select the first wavelength

X = fnirs_best_channels.values[:, 0, :]

print(f"Shape of data for ICA-ERBM: {X.shape}")

Shape of data for ICA-ERBM: (30, 2616)

/opt/miniconda3/envs/cedalion_250922/lib/python3.11/site-packages/xarray/core/variable.py:315: UnitStrippedWarning: The unit of the quantity is stripped when downcasting to ndarray.

data = np.asarray(data)

Apply ICA-ERBM

ICA-ERBM is applied to the selected channels. For the autoregressive filter used in ICA-ERBM, we use the default parameter \(p = 11\). The source estimates are then computed as \(\hat S = W \cdot X\).

[37]:

# Set filter length

p = 11

# Apply ICA-ERBM to the data

W = ICA_ERBM(X, p)

# Compute separated source as S = W * X

sources = W.dot(X)

[38]:

# Apply z-score normalization to the sources

sources_zscore = sp.stats.zscore(sources, axis=0)

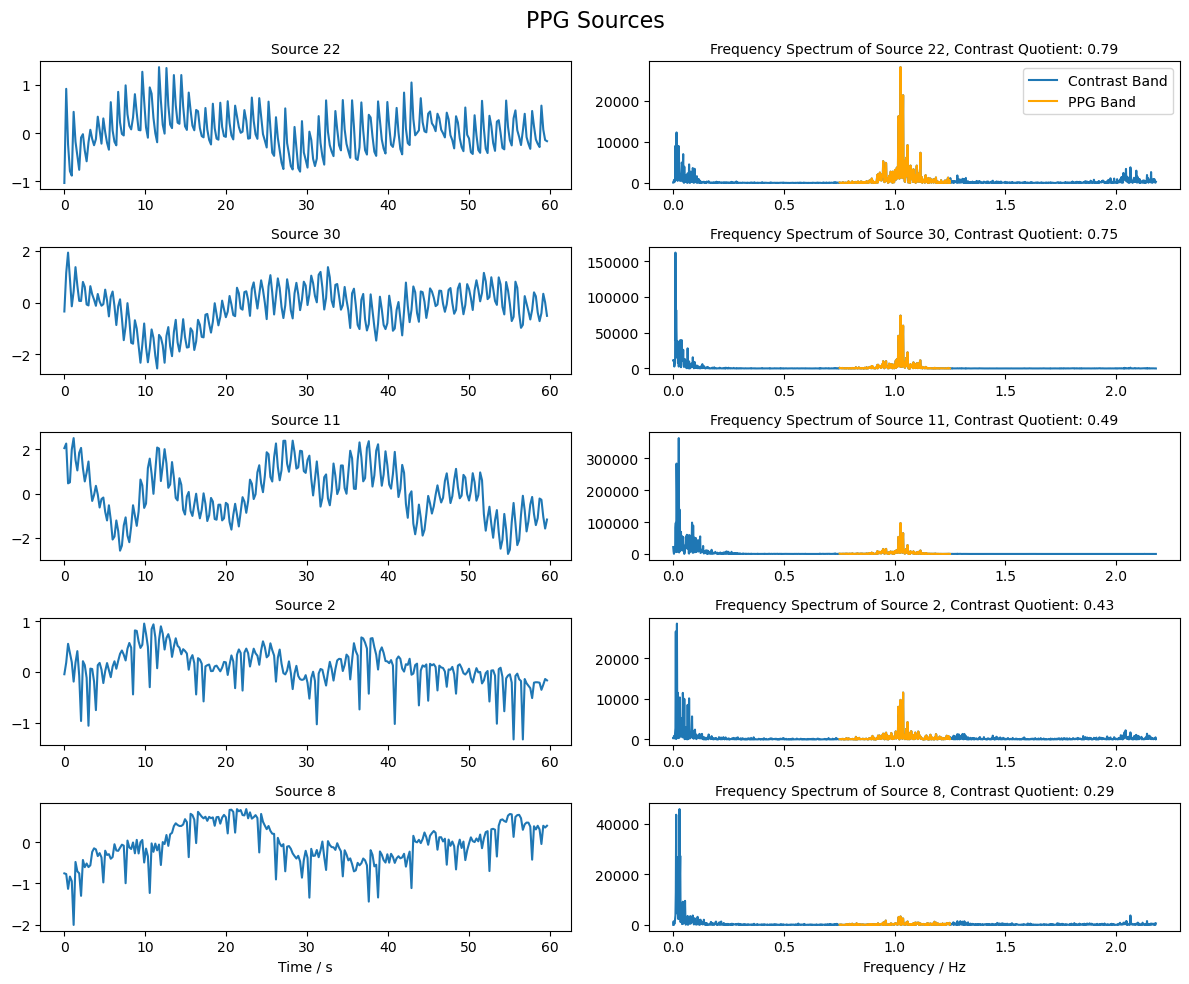

Selection of PPG Source

From the reconstructed sources, we now want to identify those that are most similar to a PPG signal. To this end, we compare the frequency band in which the PPG signal is expected to have large amplitudes with the surrounding frequency bands. The sources with the highest contrast are selected. The PPG signal is expected to exhibit high amplitudes in a frequency band around 1 Hz.

[39]:

# Compute the frequency spectrum for each source

psd_sources = np.abs(np.fft.fft(sources, axis = 1))

# The frequencies corresponding to the spectrum

freqs = np.fft.fftfreq(sources.shape[1], 1/fnirs_data_samplingrate)

# Choose the indices of frequencies that are in the ppg band (0.75 - 1.25 Hz)

ppg_band_ind = np.logical_and(freqs >= 0.75, freqs <= 1.25)

# Choose the indices of frequencies that are in the band (0 - 0.75 Hz and 1.25 - 3.0 Hz)

comp_band = np.logical_and(freqs >= 0, freqs < 0.75) + np.logical_and(freqs > 1.25 , freqs <= 3.0)

# Compute the quotient of the ppg band and the contrast band

psd_quotient = np.sum(psd_sources[:, ppg_band_ind], axis = 1 ) / np.sum(psd_sources[:, comp_band], axis = 1 )

# Choose the indices of the sources with the highest contrast

max_contrast_index = np.argsort(psd_quotient, axis = 0 )[-5:]

# Reverse the order of the indices to have the highest contrast first

max_contrast_index = max_contrast_index[::-1]

# Choose the sources with the highest contrast

ppg_sources = sources_zscore[max_contrast_index, :]

[40]:

# Plot the sources with the highest contrast and their frequency spectrum

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ppg_sources.shape[0], 2, figsize=(12, 2 * ppg_sources.shape[0]))

for i in range(ppg_sources.shape[0]):

# Plot the source for 60 seconds

samples = int(fnirs_data_samplingrate * 60 * 1)

ax[i, 0].plot( 1/fnirs_data_samplingrate * np.arange(0,samples), ppg_sources[i, :samples], label=f"Source {max_contrast_index[i]+1}")

ax[i, 0].set_title(f"Source {max_contrast_index[i] + 1}", fontsize=10)

# Plot frequency spectrum of the source

psd = np.abs(np.fft.rfft(ppg_sources[i, :])) ** 2

x_freqs = np.fft.rfftfreq(ppg_sources.shape[1], 1 / fnirs_data_samplingrate)

ax[i, 1].plot(x_freqs, psd, label="Contrast Band")

ax[i, 1].set_title(f"Frequency Spectrum of Source {max_contrast_index[i]+1}, Contrast Quotient: {psd_quotient[max_contrast_index[i]]:.2f}", fontsize=10)

# Highlight the PPG band in the frequency spectrum

highlight_ppg_band = np.logical_and(x_freqs >= 0.75, x_freqs <= 1.25)

ax[i, 1].plot(x_freqs[highlight_ppg_band], psd[highlight_ppg_band], color='orange', label='PPG Band')

ax[0, 1].legend()

ax[i, 0].set_xlabel("Time / s")

ax[i, 1].set_xlabel("Frequency / Hz")

fig.suptitle("PPG Sources", fontsize=16)

plt.tight_layout()

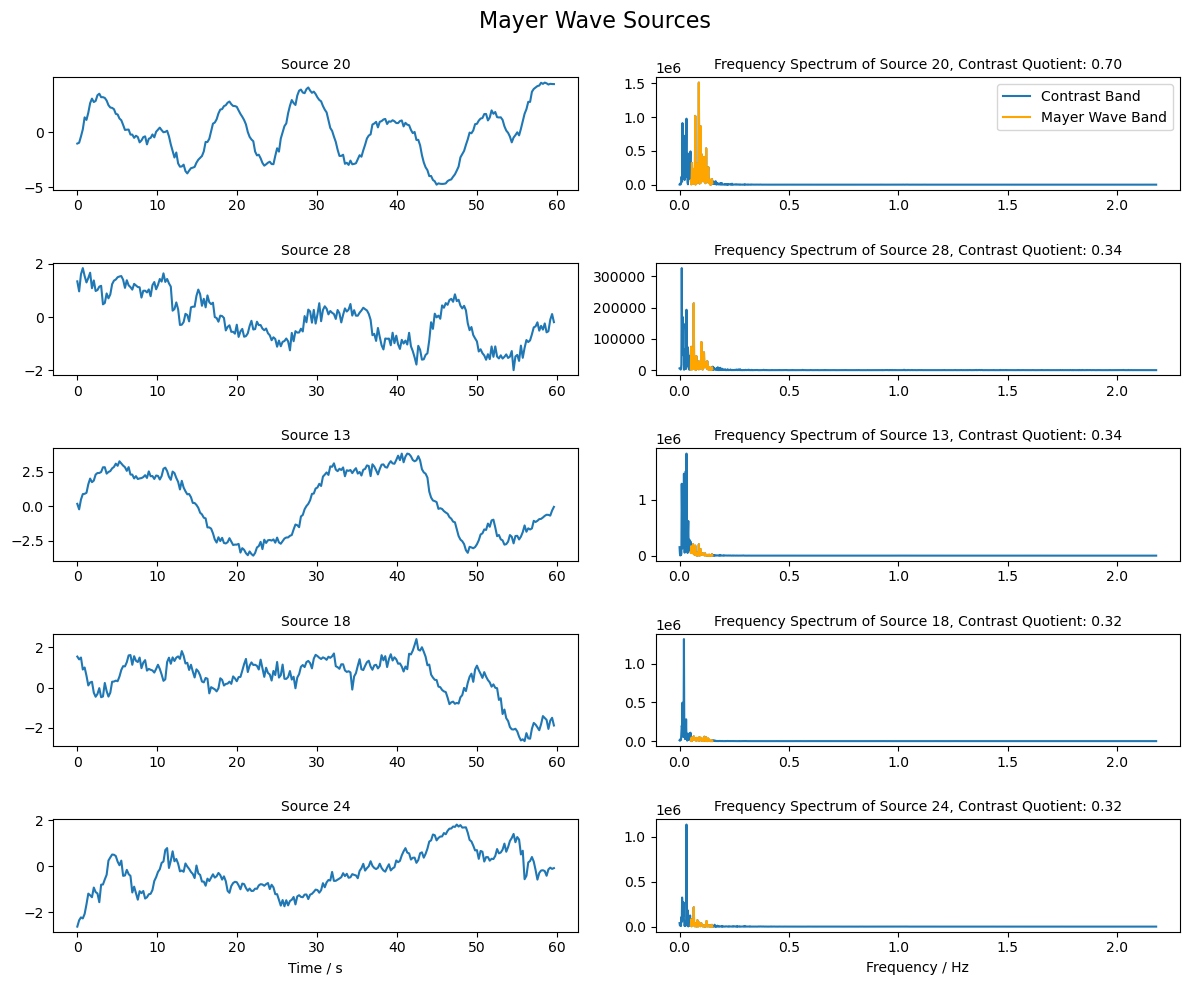

Selection of Mayer Wave Source

Mayer waves are expected to have a frequency around 0.1 Hz. Similar to the PPG sources above, we will use the contrast between the frequency band around 0.1 Hz and the surrounding bands to rank the sources and identify those that are most similar to the Mayer wave.

[41]:

# Choose the indices of frequencies that are in the Mayer Wave band (0.05 - 0.15 Hz)

mw_band_ind = np.logical_and(freqs >= 0.05, freqs <= 0.15)

# Choose the indices of frequencies that are in the band (0 - 0.05 Hz and 0.15 - 3.0 Hz)

comp_band = np.logical_and(freqs >= 0, freqs < 0.05) + np.logical_and(freqs > 0.15 , freqs <= 3.0)

# Compute the quotient of the Mayer Wave band and the contrast band

psd_quotient = np.sum(psd_sources[:, mw_band_ind], axis = 1 ) / np.sum(psd_sources[:, comp_band], axis = 1 )

# Choose the indices of the sources with the highest contrast

max_contrast_index = np.argsort(psd_quotient, axis = 0 )[-5:]

# Reverse the order of the indices to have the highest contrast first

max_contrast_index = max_contrast_index[::-1]

# Extract the sources with the highest contrast

mw_sources = sources_zscore[max_contrast_index, :]

[42]:

# Plot the sources with the highest contrast and their frequency spectrum

fig, ax = plt.subplots(mw_sources.shape[0], 2, figsize=(12, 2 * mw_sources.shape[0]))

for i in range(mw_sources.shape[0]):

# Plot the source for 60 seconds

samples = int(fnirs_data_samplingrate * 60 * 1)

ax[i, 0].plot( 1/fnirs_data_samplingrate * np.arange(0,samples), mw_sources[i, : samples], label=f"Source {max_contrast_index[i]+1}")

ax[i, 0].set_title(f"Source {max_contrast_index[i] + 1}", fontsize=10)

# Plot frequency spectrum of the source

psd = np.abs(np.fft.rfft(mw_sources[i, :])) ** 2

x_freqs = np.fft.rfftfreq(mw_sources.shape[1], 1 / fnirs_data_samplingrate)

ax[i, 1].plot(x_freqs, psd, label="Contrast Band")

ax[i, 1].set_title(f"Frequency Spectrum of Source {max_contrast_index[i]+1}, Contrast Quotient: {psd_quotient[max_contrast_index[i]]:.2f}", fontsize=10)

# Highlight the Mayer Wave band in the frequency spectrum

highlight_mw_band = np.logical_and(x_freqs >= 0.05, x_freqs <= 0.15)

ax[i, 1].plot(x_freqs[highlight_mw_band], psd[highlight_mw_band], color='orange', label='Mayer Wave Band')

ax[0, 1].legend()

ax[i, 0].set_xlabel("Time / s")

ax[i, 1].set_xlabel("Frequency / Hz")

fig.suptitle("Mayer Wave Sources", fontsize=16)

plt.tight_layout()

Single Trial Classification

The last section of this notebook demonstrates how Cedalion interfaces with scikit-learn to train a simple single-subject, single-trial classifier. The focus is on data flow: performing preprocessing with short-channel regression within a cross-validation scheme, extracting features from epochs, and passing these features to scikit-learn for training and evaluation while preserving feature metadata to allow tracing each feature back to its origin.

[43]:

from sklearn.discriminant_analysis import LinearDiscriminantAnalysis

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelEncoder

from sklearn.inspection import permutation_importance

import cedalion.models.glm as glm

import cedalion.mlutils as mlutils

[44]:

rec = cedalion.data.get_fingertappingDOT()

# assign string labels to events and pool finger-tapping and ball-squeezing trials

rec.stim.cd.rename_events(

{

"1": "Control",

"2": "Motor/Left", # "FTapping/Left",

"3": "Motor/Right", # "FTapping/Right",

"4": "Motor/Left", # "BallSqueezing/Left",

"5": "Motor/Right", # "BallSqueezing/Right",

}

)

# Keep only motor trials. Also remove the last trial so that there

# are equal numbers of trials for Motor/Left and Motor/Right

rec.stim = (

rec.stim[rec.stim.trial_type.str.startswith("Motor")]

.sort_values("onset")

.reset_index(drop=True)

.iloc[:-1]

)

display(rec.stim.groupby("trial_type").count())

display(rec.stim)

| onset | duration | value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| trial_type | |||

| Motor/Left | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Motor/Right | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| onset | duration | value | trial_type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 8.486912 | 10.0 | 1.0 | Motor/Left |

| 1 | 38.764544 | 10.0 | 1.0 | Motor/Right |

| 2 | 69.042176 | 10.0 | 1.0 | Motor/Right |

| 3 | 99.549184 | 10.0 | 1.0 | Motor/Left |

| 4 | 129.597440 | 10.0 | 1.0 | Motor/Left |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 59 | 1837.301760 | 10.0 | 1.0 | Motor/Left |

| 60 | 1868.496896 | 10.0 | 1.0 | Motor/Left |

| 61 | 1899.003904 | 10.0 | 1.0 | Motor/Right |

| 62 | 1931.116544 | 10.0 | 1.0 | Motor/Right |

| 63 | 1962.541056 | 10.0 | 1.0 | Motor/Left |

64 rows × 4 columns

Preprocessing the dataset

As in previous notebooks, motion artifacts are corrected with the TDDR and wavelet algorithms. The data is transformed into optical densities and a global component is subtracted. After bandpass filtering, concentration changes are calculated.

[45]:

rec["od"] = cedalion.nirs.cw.int2od(rec["amp"])

rec["od_tddr"] = motion.tddr(rec["od"])

rec["od_wavelet"] = motion.wavelet(rec["od_tddr"])

# see 2_tutorial_preprocessing.ipynb for channel selection

bad_channels = ['S13D26', 'S14D28']

rec["od_clean"] = rec["od_wavelet"].sel(channel=~rec["od"].channel.isin(['S13D26', 'S14D28']))

od_var = quality.measurement_variance(rec["od_clean"], calc_covariance=False)

rec["od_mean_subtracted"], global_comp = physio.global_component_subtract(

rec["od_clean"], ts_weights=1 / od_var, k=0

)

rec["od_freqfiltered"] = rec["od_mean_subtracted"].cd.freq_filter(

#rec["od_freqfiltered"] = rec["od_clean"].cd.freq_filter(

fmin=0.01, fmax=0.5, butter_order=4

)

dpf = xr.DataArray(

[6, 6],

dims="wavelength",

coords={"wavelength": rec["amp"].wavelength},

)

rec["conc"] = cedalion.nirs.cw.od2conc(rec["od_freqfiltered"], rec.geo3d, dpf)

Short-channel regression

Following the approach of von Lühmann et al. (2020), we apply a GLM to regress out physiological noise, thereby improving single-trial classification performance. To incorporate the GLM into a cross-validaton scheme, the design matrix will be masked for each cross-validation fold.

[46]:

# separate long and short channels

rec["conc_long"], rec["conc_short"] = cedalion.nirs.split_long_short_channels(

rec["conc"], rec.geo3d, distance_threshold=22.5 * units.mm

)

# define the design matrix

dms = (

glm.design_matrix.hrf_regressors(

rec["conc_long"],

rec.stim,

glm.Gamma(tau=0 * units.s, sigma=3 * units.s),

)

& glm.design_matrix.drift_regressors(rec["conc_long"], drift_order=1)

& glm.design_matrix.average_short_channel_regressor(rec["conc_short"])

)

dms

[46]:

DesignMatrix(common=['HRF Motor/Left','HRF Motor/Right','Drift 0','Drift 1','short'], channel_wise=[])

The dataset has 64 trials, with equal numbers of “Motor/Left” and “Motor/Right” conditions. In the following this dataset is split into 4 folds using the function mlutils.cv.create_cv_splits.

For each fold, a masked design matrix is created by setting the time segment used for testing to zero.

The GLM parameters are estimated and the signal components explained by nuisance regressors are subtracted.

Finally, the time series is segmented into epochs, yielding for each cross-validation fold an array of samples, to which the trial information required for training is appended as additional coordinates.

[47]:

n_splits = 4

before = 5 * cedalion.units.s

after = 25 * cedalion.units.s

cv_folds = []

for i_split, (df_stim_train, df_stim_test) in enumerate(

mlutils.cv.create_cv_splits(rec.stim, n_splits)

):

# short-channel regression (SCR):

# zero-out design matrix in test segment

dms_masked = mlutils.cv.mask_design_matrix(

dms,

df_stim_test,

before=before,

after=after,

)

# fit long channels with masked design matrix

result = glm.fit(rec["conc_long"], dms_masked, noise_model="ols")

# compute component explained by short-channel regressor

short_component = glm.predict(

rec["conc_long"],

result.sm.params.sel(regressor=["short", "Drift 0", "Drift 1"]),

dms_masked,

)

short_component = short_component.pint.quantify(rec["conc_long"].pint.units)

# subtract short component

conc_long_scr = rec["conc_long"] - short_component

# split time series into epochs

epochs = conc_long_scr.cd.to_epochs(

rec.stim,

["Motor/Left", "Motor/Right"],

before=before,

after=after,

)

# baseline correction

baseline = epochs.sel(reltime=(epochs.reltime < 0)).mean("reltime")

epochs = epochs - baseline

# assign train-/test-set membership...

is_train = np.zeros(epochs.sizes["epoch"], dtype=bool)

is_test = np.zeros(epochs.sizes["epoch"], dtype=bool)

is_train[df_stim_train.index.values] = True

is_test[df_stim_test.index.values] = True

# ... and digitized trial labels ...

label_encoder = LabelEncoder()

y = label_encoder.fit_transform(epochs.trial_type.values)

# ... as coordinates to the DataArray

epochs = epochs.assign_coords(

{

"is_train": ("epoch", is_train),

"is_test": ("epoch", is_test),

"y" : ("epoch", y)

}

)

cv_folds.append(epochs)

98%|███████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████▋ | 43/44 [00:00<00:00, 440.45it/s]

98%|███████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████▋ | 43/44 [00:00<00:00, 447.75it/s]

98%|███████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████▋ | 43/44 [00:00<00:00, 447.00it/s]

98%|███████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████▋ | 43/44 [00:00<00:00, 424.21it/s]

98%|███████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████▋ | 43/44 [00:00<00:00, 400.19it/s]

98%|███████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████▋ | 43/44 [00:00<00:00, 441.67it/s]

98%|███████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████▋ | 43/44 [00:00<00:00, 447.72it/s]

98%|███████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████▋ | 43/44 [00:00<00:00, 431.98it/s]

For each cross-validation fold the epoched time series looks like this:

[48]:

cv_folds[0]

[48]:

<xarray.DataArray (epoch: 64, chromo: 2, channel: 44, reltime: 132)> Size: 6MB

[µM] 0.06823 0.04856 0.04232 0.03702 0.03248 ... 0.04141 0.0395 0.03601 0.03161

Coordinates:

* reltime (reltime) float64 1kB -5.038 -4.809 -4.58 ... 24.5 24.73 24.96

trial_type (epoch) <U11 3kB 'Motor/Left' 'Motor/Right' ... 'Motor/Left'

* chromo (chromo) <U3 24B 'HbO' 'HbR'

* channel (channel) object 352B 'S1D6' 'S1D8' 'S2D5' ... 'S14D25' 'S14D27'

source (channel) object 352B 'S1' 'S1' 'S2' 'S2' ... 'S13' 'S14' 'S14'

detector (channel) object 352B 'D6' 'D8' 'D5' 'D9' ... 'D28' 'D25' 'D27'

is_train (epoch) bool 64B False False False False ... True True True True

is_test (epoch) bool 64B True True True True ... False False False False

y (epoch) int64 512B 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 ... 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0

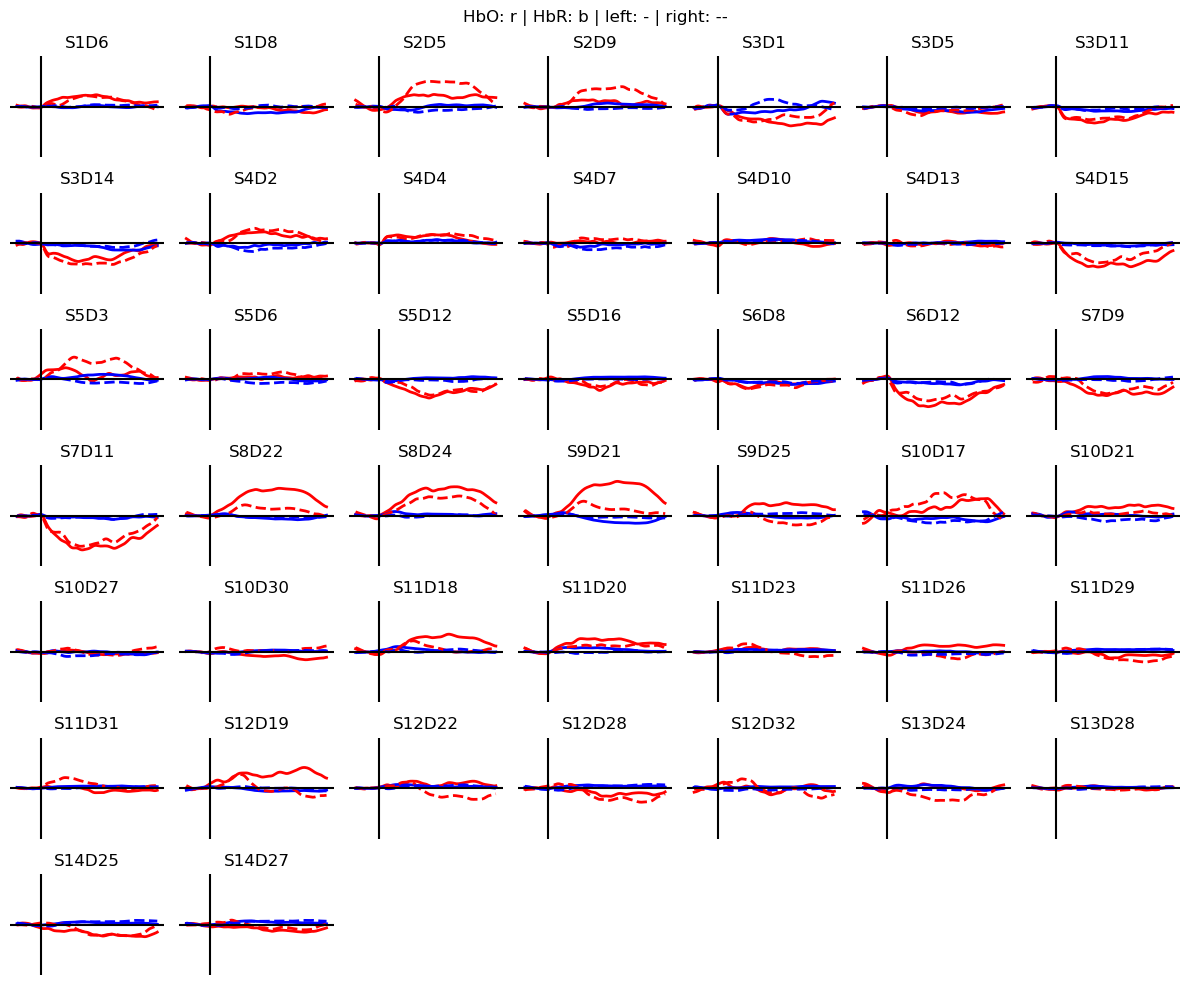

Dimensions without coordinates: epochThe hemodynamic response to the two motor tasks can be visualized by block-averaging these epochs.

[49]:

blockaverage = cv_folds[0].groupby("trial_type").mean("epoch")

# Plot block averages. Please ignore errors if the plot is too small in the HD case

noPlts2 = int(np.ceil(np.sqrt(len(blockaverage.channel))))

f,ax = plt.subplots(noPlts2,noPlts2, figsize=(12,10))

ax = ax.flatten()

for i_ch, ch in enumerate(blockaverage.channel):

for ls, trial_type in zip(["-", "--"], blockaverage.trial_type):

ax[i_ch].plot(blockaverage.reltime, blockaverage.sel(chromo="HbO", trial_type=trial_type, channel=ch), "r", lw=2, ls=ls)

ax[i_ch].plot(blockaverage.reltime, blockaverage.sel(chromo="HbR", trial_type=trial_type, channel=ch), "b", lw=2, ls=ls)

ax[i_ch].grid(1)

ax[i_ch].set_title(ch.values)

ax[i_ch].set_ylim(-.3, .3)

ax[i_ch].set_axis_off()

ax[i_ch].axhline(0, c="k")

ax[i_ch].axvline(0, c="k")

for i in range(len(blockaverage.channel), len(ax)):

ax[i].set_axis_off()

plt.suptitle("HbO: r | HbR: b | left: - | right: --")

plt.tight_layout()

For each of the 64 epochs there are \(N_{chromo} \times N_{channel}\) time traces. From these time traces, features must get extracted.

The function mlutils.features.epoch_features calculates common features of the hemodynamic response, such as slope, mean, maximum, minimum and area under the curve. For each feature type, a time range can be specified, over which the feature is calculated. In the present case, this yields features for each channel and chromophore, which are then stacked into a single feature dimensions. The resulting array has the shape expected by scikit-learn, (\(N_{samples}, N_{features}\)).

[50]:

X = mlutils.features.epoch_features(

cv_folds[0],

feature_types=["slope", "mean", "max", "min", "auc"],

reltime_slices={

"slope": slice(0, 9),

"mean": slice(3, 10),

"max": slice(2, 8),

"min": slice(2, 8),

},

)

X

[50]:

<xarray.DataArray (epoch: 64, feature: 440)> Size: 225kB

0.02127 -0.01976 0.009303 -0.007574 -0.01678 ... 0.07023 -0.04713 0.1401 0.214

Coordinates:

trial_type (epoch) <U11 3kB 'Motor/Left' 'Motor/Right' ... 'Motor/Left'

source (feature) object 4kB 'S1' 'S1' 'S2' 'S2' ... 'S13' 'S14' 'S14'

detector (feature) object 4kB 'D6' 'D8' 'D5' 'D9' ... 'D28' 'D25' 'D27'

is_train (epoch) bool 64B False False False False ... True True True

is_test (epoch) bool 64B True True True True ... False False False

y (epoch) int64 512B 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 ... 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0

* feature (feature) object 4kB MultiIndex

* feature_type (feature) object 4kB 'slope' 'slope' 'slope' ... 'auc' 'auc'

* chromo (feature) <U3 5kB 'HbO' 'HbO' 'HbO' ... 'HbR' 'HbR' 'HbR'

* channel (feature) object 4kB 'S1D6' 'S1D8' ... 'S14D25' 'S14D27'

Dimensions without coordinates: epochDuring stacking, the coordinates of the 'chromo' and 'channel' dimensions don’t get lost. They are combined and reassigned to the new 'feature' dimension. This means that for every feature in X, you can trace back which channel and chromophore it originated from.

[51]:

X.feature

[51]:

<xarray.DataArray 'feature' (feature: 440)> Size: 4kB

MultiIndex

Coordinates:

source (feature) object 4kB 'S1' 'S1' 'S2' 'S2' ... 'S13' 'S14' 'S14'

detector (feature) object 4kB 'D6' 'D8' 'D5' 'D9' ... 'D28' 'D25' 'D27'

* feature (feature) object 4kB MultiIndex

* feature_type (feature) object 4kB 'slope' 'slope' 'slope' ... 'auc' 'auc'

* chromo (feature) <U3 5kB 'HbO' 'HbO' 'HbO' ... 'HbR' 'HbR' 'HbR'

* channel (feature) object 4kB 'S1D6' 'S1D8' ... 'S14D25' 'S14D27'Training and Evaluating a LDA classifier

For each cross-validation fold, extract features, train the classifier and estimate classification accuracy.

[52]:

accuracies = []

for epochs in cv_folds:

# extract features

X = mlutils.features.epoch_features(

epochs.sel(chromo="HbO"), # HbO only

feature_types=["slope", "max", "mean"],

reltime_slices={

"slope": slice(0, 9),

"mean": slice(3, 10),

"max": slice(2, 8),

},

)

# separate train and test sets

X_train = X[X.is_train]

y_train = X_train.y

X_test = X[X.is_test]

y_test = X_test.y

# train a LDA classifier

clf = LinearDiscriminantAnalysis(n_components=1, solver='lsqr', shrinkage="auto")

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

# evaluate perfomance

accuracy = clf.score(X_test, y_test)

accuracies.append(accuracy)

print(f"#train: {len(y_train)} #test: {len(y_test)} #features: {X_train.shape[1]} accuracy: {accuracy}")

print()

print(rf"average accuracy over cross-validation splits: {np.mean(accuracies):.3f} ± {np.std(accuracies):.3f}")

#train: 48 #test: 16 #features: 132 accuracy: 0.8125

#train: 48 #test: 16 #features: 132 accuracy: 0.8125

#train: 48 #test: 16 #features: 132 accuracy: 0.6875

#train: 48 #test: 16 #features: 132 accuracy: 0.8125

average accuracy over cross-validation splits: 0.781 ± 0.054

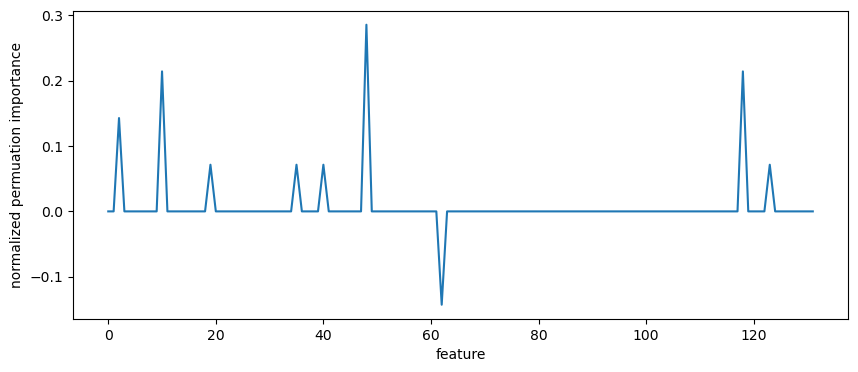

What did it learn?

One way of estimating feature importance is the sklearn function permuatation_importance. It permutes feature columns and assesses the effect on the classification accuracy.

[53]:

result = permutation_importance(

clf, X_test, y_test, scoring="accuracy", n_repeats=10, random_state=0

)

importances = result.importances_mean

importance_normalized = importances / importances.sum()

The returned metric highlights only a few important features:

[54]:

plt.figure(figsize=(10,4))

plt.plot(importance_normalized)

plt.xlabel("feature")

plt.ylabel("normalized permuation importance");

Use the preserved coordinates to identify these features:

[55]:

X_train.feature[importance_normalized != 0]

[55]:

<xarray.DataArray 'feature' (feature: 9)> Size: 72B

MultiIndex

Coordinates:

chromo <U3 12B 'HbO'

source (feature) object 72B 'S2' 'S4' 'S6' 'S11' ... 'S6' 'S11' 'S11'

detector (feature) object 72B 'D5' 'D7' 'D12' ... 'D8' 'D18' 'D31'

* feature (feature) object 72B MultiIndex

* feature_type (feature) object 72B 'slope' 'slope' 'slope' ... 'mean' 'mean'

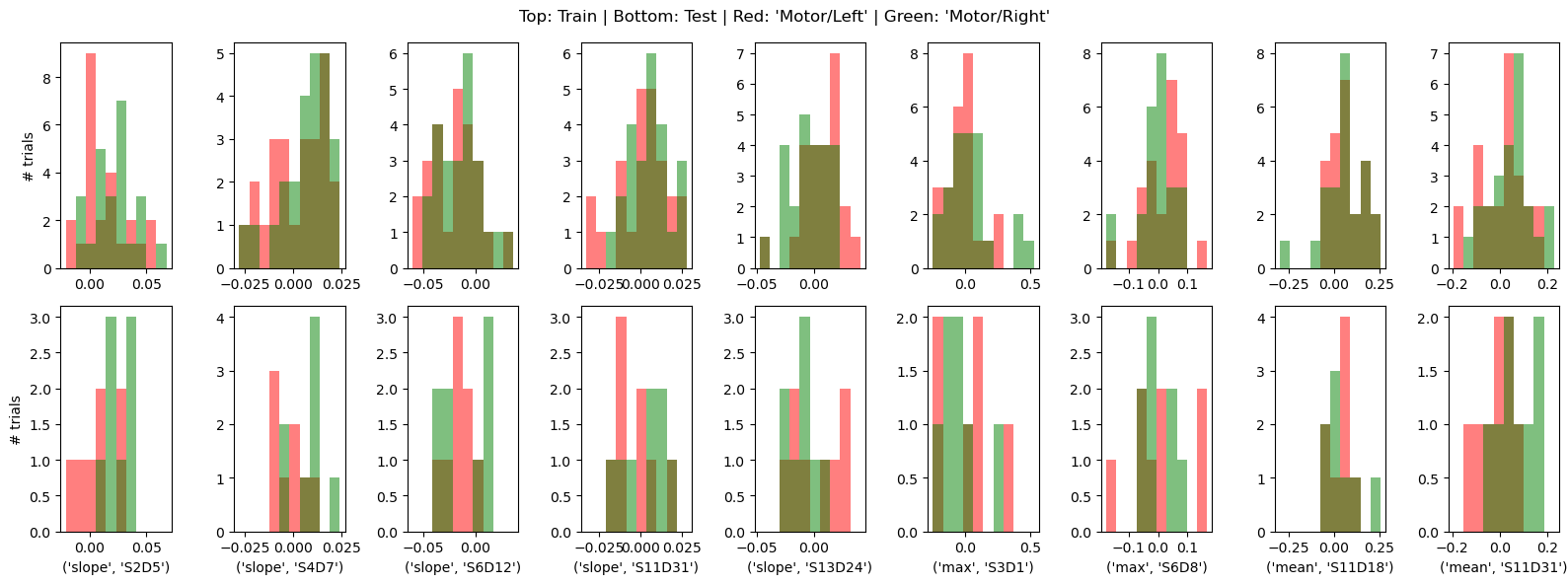

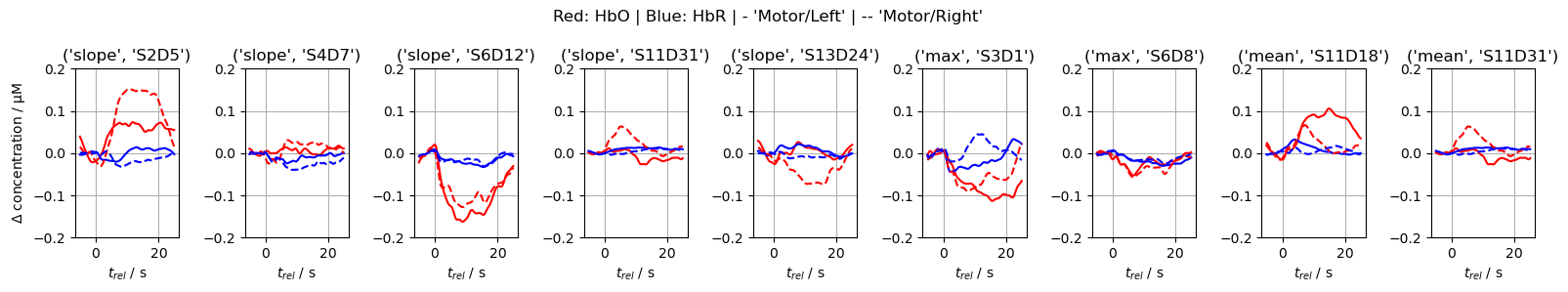

* channel (feature) object 72B 'S2D5' 'S4D7' ... 'S11D18' 'S11D31'By visualizing the feature distributions and the block-averaged epochs of the corresponding channels, we can observe that the HRFs in these channels, as well as the derived features, indeed have discriminative power.

[56]:

important_features = X_train.feature[importance_normalized != 0].values

f, ax = plt.subplots(2, len(important_features), figsize=(16,6))

for i, ftr in enumerate(important_features):

xx_train = X_train.loc[:, ftr]

xx_test = X_test.loc[:, ftr]

bins = np.linspace(xx_train.min().item(),xx_train.max().item(), 11)

ax[0,i].hist(xx_train[xx_train.trial_type == "Motor/Left"], bins,fc="r", label="Motor/Left", alpha=.5)

ax[0,i].hist(xx_train[xx_train.trial_type == "Motor/Right"], bins, fc="g", label="Motor/Right", alpha=.5)

ax[1,i].hist(xx_test[xx_test.trial_type == "Motor/Left"], bins,fc="r", label="Motor/Left", alpha=.5)

ax[1,i].hist(xx_test[xx_test.trial_type == "Motor/Right"], bins, fc="g", label="Motor/Right", alpha=.5)

ax[1,i].set_xlabel(str(ftr))

ax[0,0].set_ylabel("# trials")

ax[1,0].set_ylabel("# trials")

f.suptitle("Top: Train | Bottom: Test | Red: 'Motor/Left' | Green: 'Motor/Right'");

plt.tight_layout()

f, ax = plt.subplots(1, len(important_features), figsize=(16,3))

for i, ftr in enumerate(important_features):

ax[i].plot(blockaverage.reltime, blockaverage.sel(channel=ftr[1], chromo="HbO", trial_type="Motor/Left"), "r-")

ax[i].plot(blockaverage.reltime, blockaverage.sel(channel=ftr[1], chromo="HbR", trial_type="Motor/Left"), "b-")

ax[i].plot(blockaverage.reltime, blockaverage.sel(channel=ftr[1], chromo="HbO", trial_type="Motor/Right"), "r--")

ax[i].plot(blockaverage.reltime, blockaverage.sel(channel=ftr[1], chromo="HbR", trial_type="Motor/Right"), "b--")

ax[i].set_ylim(-.2,.2)

ax[i].grid()

ax[i].set_title(ftr)

ax[i].set_xlabel("$t_{rel}$ / s")

ax[0].set_ylabel(r"$\Delta$ concentration / µM")

f.suptitle("Red: HbO | Blue: HbR | - 'Motor/Left' | -- 'Motor/Right'");

plt.tight_layout()